The last twelve months were, market-wise, interesting. Multiple things have happened that contributed to changes in my thinking-process. Refining thoughts and the mental mechanism I utilize to approach portfolio management should lead to success, or at least that is my hypothesis. Continuous learning allows for building more solid premises. Given time, compound interest sharpens them to the point where chances of error are minimum.

My intention for these writings is to share what and how I think about investing. Further, my deep focus on the ‘Why’ of things makes me try to express the reasoning behind the decisions I make. We do not control outcomes, only the input, theoretical in the context of this field. It is, then, the input which needs to become the unit of analysis. However, the output must not be de-estimated as it composes the only yardstick for process-evaluation.

In case you prefer the PDF version:

Performance

The partnership finished its second calendar year, with inception being on the 25th of January of 2022. Naturally, proper conclusions cannot be drawn from such a short timeframe. Only if one does something repeatedly can we roughly determine if it is the person who’s causing the outcome. But, in two years, too few scenarios have played themselves out, creating a large room for randomness to rule outcomes. It is consequently naïve to believe that one’s behavior is the causal factor, as causality must be maintained throughout different composites of variables. I even suspect that not even in the long run will performance be an accurate manifestation of skill. However, I am not sure I’ll be able to find a better proxy.

During 2023, the portfolio’s value increased by 45.92%, after having dropped by 15.32% in 2022. Cumulative performance stands at 23.56% since inception on the 25th of January of 2022. On the other hand, the S&P 500 has returned 11.5% in the comparable period. I find that comparisons such as this are ultimately irrelevant, but provide a realistic parameter for perspective. Lastly, a moderate understanding of arithmetic and history suggests that returns experienced in 2023 are on the far-right tail. They are strongly unlikely to be repeated. Expecting such a thing is unrealistic and will guarantee disappointment.

Note: There is some element of miscalculation in 2022’s return trajectory because of a capital injection that occurred in June of that year.

Returns have been relatively satisfactory, considering my limited knowledge. Nevertheless, I find no merit in such results as I believe that randomness heavily outweighs the potential presence of fairly decent decisions. Fundamental underlying performance is what will somewhat give a better sense of whether one is right or wrong with business’ selection. At the moment, I attribute 70-80% of the out-performance differential to a fortunate starting date.

The markets experienced a bear market in 2022. Having begun the partnership in January of that year is nothing but a coincidence, which strongly influenced results. It is reasonable to think that the S&P presents less volatility than its underlying individual components. Therefore, by one buying individual businesses in a bear market, chances are quite high of outperforming the index in the short run. Investing in businesses after a 30-40-50% drawdown, when the index falls 20%, might be a decent recipe that’s prescribable for achieving profitable short-term results. In the same context, purchasing good businesses might even prove profitable in longer time horizons.

However, there is an element I do not intend to overlook. Graham wisely stated that everything that’s easily explained and replicable, by definition, will not last long. If what we did was stupidly easy, everyone would do it, and then alpha would be lost. Francois Rochon hypothesized that there may exist a gene, which he calls the tribal gene, that genetically ‘forces’ one to follow the crowds. Psychological viruses seem to exist and are rapidly transmitted, causing irrational behavior over temporary periods. During 2022, we not only proceeded against the investment community, but did so at what I would consider as rational prices. Patience, courage, and confidence were shown. Otherwise, returns wouldn’t have followed the pattern they did.

Now I ask myself, can these traits be mistakenly confused and caused by ignorance, foolishness and recklessness? I think the answer is, unfortunately, positive. Not understanding the consequences of one’s actions could lead to acting because of an incorrect appraisal of reality. Hence, again, the importance of relying on time’s judgement. Only after several decades will I be suited, and not even with a high degree of confidence, to conclude whether or not such traits are innate or if they were a false reflection.

In any case, no doubts should be held as to whether or not I am taking what I believe is the course of action that will yield the biggest results. Questioning, and not taking things for granted, is the practice I believe compounds at the highest rates in this field. If I were to take traits and other elements for granted, I would not have learned as much in 2023, and would be easier prey to psychological biases. Furthermore, I think it would be a certain long-term condemn.

Where We Come From and Where We are Going

Life follows a curious pattern. Learning is the application of newly acquired knowledge. Nevertheless, it is only in hindsight that we can analyze applied knowledge and infer whether or not it was appropriate to do so. Mistakes are a byproduct of incorrect decisions, which are derived from previously untested information. Even if we were to correct mistakes prior to them impacting our performance, we will not be sure if what we applied was an authentic patch or not, nor if water was leaking into the ship in the first place.

In the realm of investing, it is no different. We can make buying/selling/holding decisions that we think will improve the expected return of the portfolio. Others could be made for risk to be minimized, even if that means to sacrifice expected growth. The latter might seem illogical, but it could be required for errors to be avoided.

Rationality appears to be a mental state, the one desired for investing, and human emotion is the element that causes a disruption of such state. Therefore, it becomes rational to take irrational action for human emotion to not interfere with the task at hand. Ultimately, it simply boils down to knowing oneself and detecting undesired triggers.

Getting acquainted with non-lived history provides, in most cases, insights we would not be able to obtain otherwise. On the other hand, personally lived history provides fertile soil for deep analysis. By studying our past decisions and hypotheses, it might be possible to tell if the path taken was the correct one, given information available at the time. Consequently, I will lay down the portfolio’s evolution, starting with the initial ideal one, and go through the reasoning behind the structural changes. Finally, I will articulate what I think is the mid-term, but terminal, obstacle the partnership’s future performance is facing and what’s the plan to address it.

The first ‘ideal portfolio’, the target, created in January of 2022, looked like this

Note: We never got to a portfolio that looked like this because I made changes to the ideal one.

Note: Some positions were inherited, like a 10% in Apple and 17% in the SPY, for which a rotation was required.

Infinite questions: “What even is this?”, “Why did I place so much weight on ETFs? Why not index in that case?”, “Isn’t this something like the SPY with excess weight on the big names?”, among others.

Having lived 2021 growth stocks’ pop made me realize how dangerous it is to be invested in things one does not understand and to de-estimate history. If proper reading had been done, I suspect it would have come naturally to beware of the market’s state. I am aware of the effects of hindsight bias, but I am still somewhat confident of the prior statement. In any case, the lesson I learned was that I knew close to nothing. My preoccupation and focus in January of 2022 was, then, to minimize the portfolio’s risk by limiting its exposure to my ignorance, because I think it is the latter what causes risk to be present. To that end, three measures were taken:

Cash would be deployed slowly, in a DCA-like fashion, focusing on averaging allocation below fair values.

The portfolio should consist of as low-risk assets as possible. At the time, I had the sense that the chances of suffering permanent losses of capital were directly tied to, in the world of equities, brand value.

With value preservation in mind, and not fully understanding the effects of diversification, several ETFs were included. Furthermore, my intention for the portfolio was to moderately replicate the S&P 500’s behavior.

All three further combined to provide me with time to learn and apply knowledge. As a consequence of my reads, the ‘ideal portfolio’ was modified, and several times. This is generally not recommended. Nevertheless, each ideal portfolio that was crafted was done so with the tools available at the time of crafting. I suspect that, every time one’s arsenal gets re-equipped, constructions need to be revisited and improved, if possible. My problem was the large information deficit that I had and still do.

The fact of me having too few tools caused a continuous relative flood of equipment. With each wave, my prior craft was analyzed and polished, which caused a high turnover in the ideal portfolio, and a moderate one in the weight of positions. A high turnover rate is ultimately undesired. Furthermore, making too many decisions must be avoided. It is rather unlikely to be profitable on the average decision if we split mental resources among multiple of them. Too much activity might be the single largest detractor to investors’ performance.

On practice, the desired result was achieved. On the theoretical front, I think it wasn’t. The experienced drawdown in 2022 was less severe than what it could have been if I were to follow intuition. Regarding the latter, nature embedded within us wisdom acquired throughout millions of years. Nonetheless, never has nature dealt with stock-investing issues. Therefore, it’s irrational to think one’s intuition, at the beginning of their journey, is well trained and could be relied upon.

By the end of 2022, first year of management, the actual portfolio looked like the following, with 15-20% in cash:

With learning, a couple of things happened. Knowledge started lighting previously dark places, for which I started deriving more comfort from different practices. An element of concentration was starting to be noticeable, and research made overall positions tilt towards a composition of well-known “quality compounders”. Furthermore, weights started reflecting availability factors adjusted by perceived quality.

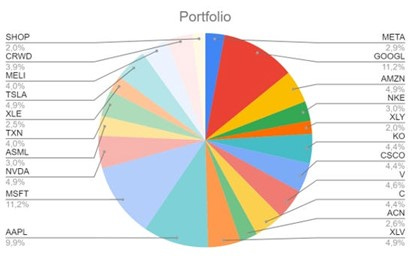

During 2023, the prior trends made themselves fully visible. Concentration appears to be the consequential effect of confidence in judgment. The remaining 15-20% cash was deployed in the first three quarters of the year and raised back again in the last one. Even though, once removed ETFs from the portfolio, companies held were sound, there are many of them that I struggle to see delivering an above-market fundamental performance over the long run. This is of extreme relevance if one’s intention is to make outperformance as likely an event as possible. By the end of the year, the portfolio held was the following:

For the above-mentioned reason, some companies were removed from the portfolio. Five to ten years down the road, I cannot picture fundamental outperformance. Moreover, some other businesses, still held, I suspect will experience good fundamental performance over the next 5-10 years. However, I think they will run out of fuel for a subsequent alike period. This puts a theoretical ceiling and deadline to a hypothetical fundamental outperformance.

Naturally, because things cannot grow forever, by opting to research and buy mostly large companies I was rapidly propelling myself into a future sudden stop. With each portfolio rebalancing during the past 2 years, the deadline was pushed forward, but staying in multiple saturated industries is a likely recipe for failure. Therefore, I started looking at other places, where I think there is a longer runway ahead. Some of the companies and industries I have been researching are:

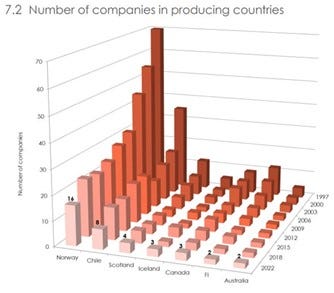

The salmon farming industry. I found it immensely interesting, with prominent players having good returns on capital. The industry has been tending towards consolidation, with the number of competitors falling around 77% in countries like Norway. This was caused, I suspect, by the heavy regulatory environment, biological issues and the capital intensity that’s required. Lastly, salmon has an uncapped demand, shown by how commercialized value outpaces volume.

BIM Software Industry. Building information modeling is utilized for the architecture, engineering and construction (AEC) industry. The fundamentals of the software, with network effects involved in most platforms, led the industry towards concentration, with Autodesk holding over 50% of the market. However, because of the depth with which the software can be created, a large part of the remaining market share is composed of niches, each being dominated by one or two companies. The efficiency BIM brings to this massive industry, alongside the low overall penetration, makes me conclude there’s still a long runway ahead. Furthermore, BIM started being utilized in other industries, like digital media creation. Most of these imply large-and-growing addressable markets

Winmark is a company that possesses different brands for resale retail stores. They do not operate them themselves. Rather, the team looks for committed and resourceful entrepreneurs to open them and run them, allowing them to utilize their brands. Agreements last for 10 years and the renewal rate has stayed above 95% for 16 years. Winmark charges a royalty fee of 4-5% of the franchise sales, generally. Even though growth has been relatively low, each franchise that’s opened supposes a predictable stream of cash flow for Winmark for the subsequent 10 years and, in most cases, longer. I suspect the trade off between growth and resilience is worth it in this case.

Topicus is a spinoff from Constellation Software and follows its business model. They are serial acquirers of vertical market software (VMS) businesses. The targets are generally small companies, deals of around 5M, with a diversified customer base, that offer mission critical software, have low customer attrition, have fragmented competition with relatively small addressable markets, some organic growth potential, and capital constrained competitors. The small deal-size offers a unique advantage as there is, or at least in the past, limited competition for them, and can be done at very low cashflow multiples. Constellation Software, which has been in business for around 30 years, has consistently achieved very high returns on capital.

Burford Capital is a company that deploys capital in the legal industry. They are addressing, mainly, two issues. (1) Small and mid-sized companies don’t count or are not interested in utilizing cash from their balance sheet to finance litigations, which are generally costly and; (2) Most corporations are now preferring to pay law firms for success, but law firms have limited balance sheets to pay for their lawyers and prefer the hourly pay. Burford bridges both gaps and charges a fee and a share of the proceeds. The unique spot in which it’s in allows the business to generate high IRRs with a portfolio of uncorrelated assets.

My intention with these businesses, and some more I will be researching, is to extend the portfolio’s life expectancy of excess returns. Long-term investment out-performance seemingly comes from higher returns on capital than average. In the short and mid-term, alpha might arise from a mix of the former and a below-fair-value purchase price. Regarding the latter, the element of the financial community’s appraisal is always present.

It then becomes a matter of expanding the universe of investable companies, which is tied to one’s circle of competence. A major mistake is to step outside of it. Not even in certainty there is certainty. How, then, can one expect to find certainty in uncertainty? Living outside one’s own frontiers of knowledge will likely trigger irrational action. Further, guarantees of capital preservation are non-existent in such a realm.

Competition

In “The Use of Knowledge in Society”, Hayek posits the dilemma societies face when making conjunct decisions. Resources are scattered across populations, yet prices need to be set so that they are in equilibrium with all inhabitants. Namely, there are two approaches to solving the problem:

A centralized approach implies for a person, or entity, to be given all information available and continuously updated. After proper processing, the person sets prices.

A decentralized approach takes the allegorical shape of Smith’s invisible hand.

Because we are limited beings and cannot manage data in its disaggregated and dynamic form, the pricing mechanism solves society’s issue by decentralization. All agents in the economy participate in setting prices by sending signals, in the form of buying, selling, or doing nothing. This statement entails a fundamental and inescapable truth of the stock market.

When investing, we are necessarily sending signals. And it is the case that all business’ prices are set in accordance with agent’s expectations of the companies’ underlying future cash flows. Hence, to achieve profitable investing, our signals need to be in dissonance with that of the market. There needs to exist a future we believe will play out that the market is overlooking and therefore mispricing the asset in question. Otherwise, an investor will not experience excess returns if the future is exactly like what prices suggest.

The inescapable truth, then, is that we compete with other signal-senders. Understanding this phenomenon could lead to the conclusion that our job, as investors, is to look for as weak a competition as possible. Human nature’s innate pride pushes us, however, towards the other direction. We seek competition and are wired for even fighting for honor. Investment decisions must be made under these considerations for them not to cloud our judgment.

If I were to pull the prior thread, incentives would tilt one to try select an arena where the odds of winning are the highest. A theoretically ideal path forward would be to find a battlefield where one is the only battler. In that scenario, if the signal sent is in accordance with the soundness of the underlying business, the investor will win. To the contrary, a dense fog emerges when more and more signals are sent. The lack of clarity derives in a very intricated appreciation of the asset, which corresponds to larger and larger groups of people. Further, the likelihood is higher for the arena to become the playground of highly intelligent people, many of whom one would not be wise in combating.

Philosophically, what was stated appears to be true. Nevertheless, history has recurrently proven that such arenas are occasionally infested by a virus that causes misapprehensions by most competitors. Consequently, there are two sides to consider. On the one hand, it is true that more high-quality investors compete in more crowded arenas, but more people who are propense to fall victim to this virus are here as well. I then arrive to a point where I do not know which territory to select. When sending a signal, my counterpart could either be a genius or an infant. The only thing that seems to be reasonable and will work everywhere is a two-step recipe:

Become virus-resistant. If it is genetic, I can simply hope for the configuration to be there. Recent history pointed in the correct direction, which is confidence-inspiring, but time will tell. If it is not genetic, it is in an investor’s best interest to find what the origin of such virus is and how to cure it. Importantly, this must be done beforehand, as the disease obfuscates one’s sight to the point where the brain does not properly function while in this temporary state.

Improve the quality of one’s signals. There is an objective element as to how solid are our decisions. Since the framework for analysis does not physically change, working on improving its quality seems like a good measure.

My Biggest Mistakes

Inspired by Rochon’s letters, I will take a step back and try to tell the most relevant mistakes I have made so far. These will not be errors due to incorrect conclusions because those are still in trial, and the juror takes a long time to give its verdict. Rather, I will focus on two mistakes I think were caused by misanalysis and misbehavior.

Stepping Outside of my Circle of Competence

The line between what we know and what we do not is objectively clear. If our knowledge was the unit of analysis, any third-party could easily tell our mastery of different fields, or at least roughly. It would make it even easier to simply discard those fields where there’s no certainty of expertise. Unfortunately, the thing we master the most is deception. And even more unfortunately, the easiest person to fool is oneself.

In my last letter, I communicated that we had sold Nvidia in the first semester. In the second half of the year, I came across a technical thesis on how AMD might be disrupting Nvidia’s design process. After carefully going through it, I noticed I couldn’t arrive to any conclusion of my own. The root for this incapacity was clear: I did not know enough about the business. I then wondered why I even had the company in the portfolio in the past, and why was it still in the ideal portfolio.

This element’s importance cannot be understated. Only by understanding can we know what the input for a decision is. The lack thereof will have two detrimental effects, depending on the future scenario:

If it goes well, one will not know what caused that to be the case, making it unrepeatable. Further, it goes against an investor’s best interest to maximize undesired randomness because of how well-informed prices generally are.

If it goes wrong, not only will one carry a permanent loss of capital, but we will also not know what caused it. Therefore, one would be condemned to repeating the mistake. Omittable errors are only those whose nature is not ignored.

To be clear, Nvidia is not the only case where I fall prey to my own negligence. After realizing it, I have been working and will make sure to only make decisions with understood nature and input.

Not Betting in Accordance with Expected Values

This mistake is one where the jury is still out.

There are times when the business we are most confident on becomes severely mispriced. On such occasions, a rational analysis, I believe, would point in the direction of strongly increasing the position’s weight. Similarly, the inverse is true. Buffett calls these the “availability factors”, which incidentally cause one’s portfolio weighting to variate.

Mercado Libre started 2023 at almost $900 per share and, after a rally, it revisited what I considered as “cheap” prices. Even though the company’s weight in the portfolio was increased, my degree of confidence in the call was quite high, given the fair value I suspect the business has, the likelihood of the destination and trust in management. This mistake, and others of this kind, proved and I am sure will continuously prove to be expensive.

What’s curious to observe is that a 50% return might carry lower risk than an investment that generates 10%. A fine business at a low price entails less chances of a permanent loss of capital than one that’s closer to a fair price or above it. This observation came unnatural to myself, it is paradoxical, and it goes against what academia professes, but it is, I believe, true. It is up to each investor to scan the universe of businesses, determine which of them are the soundest, with good growth prospects, and then try to estimate their intrinsic value.

The Need to Act

Understandably, patience is a trait that’s hard to practice and rare to naturally possess. The temporary lack of it has motivated unwise behavior, not in the form of buying, though. An apparent necessity of action, has, for instance, made me make changes to the ideal portfolio ‘just for something to happen’, as Dostoevsky cleverly pointed out in Notes from Underground.

Not resisting the urge to act forces one into a destructive path. Because we count with limited resources and mental capacity, a sound course of action is one in which we make only a few decisions. The more we try to spread our resources by making more decisions, the more will the result tend towards an average one. It is difficult to escape below-coinflip probabilities if one acts too often in this field.

My Psychological Impediments

Although the list is extremely long, I will focus on two of them that I believe might be generating the biggest risk.

Confirmation bias, which comes in the form of an anecdote. On September, I was reached out by a person that had founded an ag-tech business 6-7 years ago. After a 30-minutes conversation, in which he explained to me what the company was about, I immediately concluded that it was theoretically poised for success.

Throughout December, I wrote the first part of a two-series case study in which I analyze whether or not theory would suggest disruption. Curiously, my mind, after tens of hours of reading and meditation, articulated its way towards my initial conclusion. It could be the case that it’s simply true, but it is something worth pointing out, as I doubt my conclusion was objectively right.

Overweighing availability. Since we are not omniscient beings, our knowledge and conclusions are limited by our learnings. This causes an objective misappreciation of the general picture. The emphasis that’s placed on the few pieces of the puzzle we are familiar with is much higher than what it would if we were to see the completeness of the board. In my case, I suspect that I am heavily overweighting the importance of some elements. Furthermore, the fact of me selecting good businesses is a byproduct of how many companies I analyze. The less amount that I research, the higher the dependence on randomness, as it will be more a matter of being fortunate in falling under one of the few solid roofs out there.

Expectations Moving Forward

A funny anecdote reveals why being mostly and continuously invested is the best path forward. Although I vividly claim and know that I have no idea about how things might play themselves out, one cannot escape speculative thoughts. I am not exempt from my mind trying to find explanations to all questions. It therefore arrives to knowingly false conclusions and does its best to justify their veracity.

In July, I spoke to one of my associates and both of us were “certain” that, considering everything, the second half’s performance would be moderately negative. Being familiar with Man’s propension to fool himself by appearing to know something he certainly doesn’t, we decided to not do anything, not selling in this case. If we were to follow our “intuition”, the mistake would have caused unmeasurable damage to performance, in all senses.

For the coming time, the only guarantee that I can make is that I will continue to polish the tools I employ for business and decision analysis. I suspect compounding will do the rest.

Personal Commentary

I needed to carefully reflect on these things I believe have caused and are causing my performance to not be optimal. That’s the only way we can improve. As much as I think these letters are fascinating to write, they are unbelievably hard. I am not sure if the next one will be in July, as the last one, or next December and make it one per year. In any case, I hope you enjoyed or found my thoughts useful.

Contact: Giulianomana@0to1stockmarket.com

Beautifully written my friend!