Aquaculture is the name given to the ‘agriculture of aquatic species’. The fundamental factor fueling the industry as a whole is human consumption. We need to ingest animal protein for our bodies to work correctly, and fish plays a huge role in this. Over the past 6 decades, per capita meat consumption has almost doubled.

Meat has been historically scarce and, therefore, expensive. However, a growing global economy has helped increase average household incomes, at the same time as increasing meat supply, making it more affordable and accessible from both ends. Moving forward, the human population is expected to continue increasing, in line with meat consumption. Curiously, because of the scarcity of land-based protein production, how environmentally unfriendly is and its higher inefficiency compared to fish’ production, fish supply and demand are expected to fairly outpace overall meat.

As observed in the chart above, the average person eats almost 2x seafood as it did half a century ago. Global production of fish has quadrupled while human population doubled, explaining this gap. And, out of the total 492M tones of the global protein consumption (estimated by the Food and Agriculture Organization), fish equated to 161M, and salmon to 2.6M.

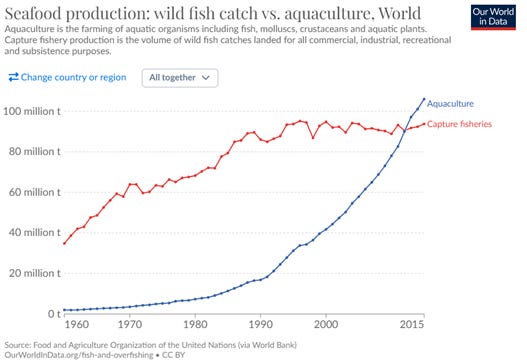

Within seafood, the two major methods for production are aquaculture and wild catch. The past six decades have been accompanied by a huge development of aquaculture, outpacing wild catch, and as of 2022, had a 56% share of seafood consumption. Specifically in salmon, about 80% of the worlds’ salmon harvest is farmed. This trend is to continue given the scalability each method supposes.

Moving forward, Mowi’s handbook states multiple trends that are expected to keep fueling salmon’s demand. Leaving aside population growth, which is the ultimate secular tailwind, there’s:

Health and aging population. Healthcare’s focus is expected to switch to prevention, leading to nutrition becoming essential. Fish, and particularly salmon, are considered to be a vital source of protein.

Growing middle class. As the average person gets richer, meat demand and kg per capita should continue to increase.

Climate change. The world has become increasingly more aware of environmental issues. As a consequence, aquaculture in general has outpaced other agricultural processes due to the high efficiency at which fish can be farmed. The latter’s carbon footprint is much lower and it consumes less liters of water per kg of meat than other animals.

Note: the table includes salmon, not fish in general

Resource efficiency. Protein retention measures ‘how much animal food protein is produced per unit of feed protein fed to the animal’. Feed conversion ratio measures how many kg of feed are needed to increase the animal’s weight by 1kg. Salmon is far superior to other animal protein sources.

Ultimately, aquaculture has fairly outgrown agriculture and, within aquaculture, salmon is one of the species that have benefited the most. Over the past 10 years, the value of salmon sold has increased at an 11% CAGR, while volume has increased at a 4% CAGR in the same period. The strong underlying and unattended demand for salmon allow for a fundamental pricing power.

“The total protein market in the world is 400M tons, out of which 2M tons is salmon. The average growth of this market could be something like 2-3%, while salmon maybe grows of 6-8%” Regin Jacobson, Bakkafrost CEO; 2018

The barriers to entry this industry are interestingly high and its natural characteristics have led to continuous consolidation. We’ll now get into the barriers…

Barriers To Entry

Salmon is not available everywhere and, moreover, not all waters where it’s available are suitable for farming. The countries that meet all conditions are Norway, Chile, Scotland, the Faroe Islands, Ireland, Iceland, Canada, USA, Tasmania and New Zealand.

To keep aquaculture’s environmental impact as low as possible, the industry has become extremely regulated. In fact, “license systems have been adopted in all areas where salmon farming is carried out”. Licenses’ implications depend on each country. Some of them have much more intricated systems than others, but the variables are generally the following:

Annual and upfront fee to operate a site. The annual fee depends on volume

Getting a license takes 5-10 years, they last for 10-20 years and can be renewed (mostly the case)

Licenses grant a number of sites to farm (4 in Norway, for example), and determine de maximum volume of fish (MAB) that can be held at sea at all times. MAB is generally dependent on water, disease conditions and particular circumstances

In parallel to companies’ reliance on licenses, the fundamentals of the average salmon producer are far from ideal. This is a very capital and resource intensive industry, demanding:

High upfront investments to get factories going. To equip one, you need cages (steel or plastic), moorings, nets, cameras, feed barge/automats and workboats

Low average EBIT margins because of the high competition at the bottom-end of the market (I suspect this, need to further dive here)

Licenses fees

Biological implications require either high levels of R&D, or complete dependence on suppliers

Continuous reinvestment to keep fish at sea at all times. Working capital investments are required for organic growth, as a larger “pipeline” of fish is needed to facilitate larger harvest volumes

Regulatory restrictions, biological issues, competition in the low-end of the market, low control of the value chain, the advantage of economies of scale, and the capital intensity of the industry have led to a continuous consolidation of players. The salmon producing industry presents all characteristics for a “winners keep winning” environment.

Note: The graph shows the number of companies producing 80% of the farmed salmon and trout in each major producing country. Notice that, for instance in Norway, the number of players dropped from almost 70 in 1997 to 16 in 2022.

Finally, here are the top 5 players in terms of volume:

Relevant Variables For Analysis

Salmon production, farming and harvesting, (the whole cycle), takes around three years. During this period, the product goes through several steps. From fertilization and early-stage growth in freshwater, to sea growth, to processing plants. Vertically integrated players will be the ones that would, theoretically, enjoy the best margins and returns, assuming a similar pricing.

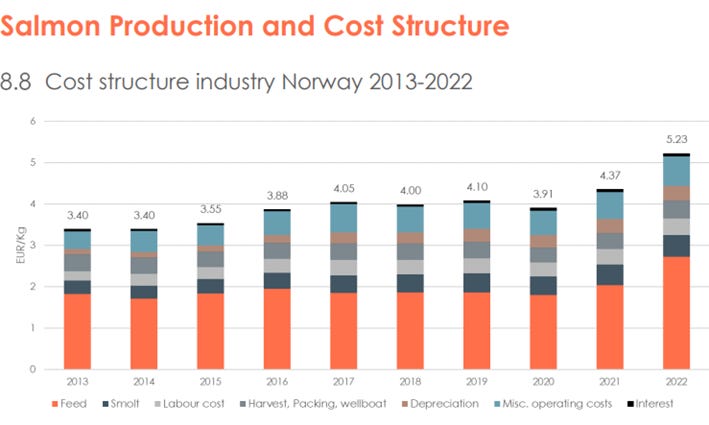

The reasoning behind this is that vertically integrated companies have the possibility to attack all cost buckets and make the process as efficient as possible. The chart below aims to show how does the cost structure of companies looks like. For example, the feed they give salmon represents almost half the cost of production. Therefore, looking for companies that develop feed in-house and achieve lower conversion rates should prove rewarding.

Similarly, the yield per smolt is an important indicator of production efficiency. It represents the harvest weight per smolt transferred to seawater. The number of harvested kilograms yielded from each smolt is impacted by diseases, mortality, temperatures, growth attributes and commercial decisions. The higher the better.

The second thing that could be worth looking at is geographical diversification, or at least avoiding extreme concentration. Salmonids face several biological risks, with some of them having unidentified causes, for which epidemies can occur and wipe out particular sites. At the same time, having license concentration in only one country makes the company very susceptible to regulation changes, which seems to happen occasionally.

Thirdly, perhaps analyzing what are the results that R&D initiatives are yielding can help shed light as to which company has the most suited team and deploy capital more optimally (speaking only about R&D). Trends such as feed conversion, survivability rates and sea lice numbers can be some elements to focus on.

Finally, value added products (VAP) is a subsegment within the salmon industry. It consists on filleting, fillet trimming, portioning, producing different cuts, smoking, marinating, breading, and depends on the factory’s technology and people employed, as it is capital intensive as well. However, it provides some sort of diversification to revenue, consumers are willing to pay for quality and it also adds stabilization to the topline because the deals are based on fixed-price contracts. Trying to infer what are companies’ approach towards VAP might prove useful. Experience and a long-term strategy of expanding here might be a desired thing to see.

Most Appealing Public Players

Mowi

Founded in 1964, Mowi is a Norwegian vertically integrated company that’s focused on farming and harvesting salmon to then sell it in multiple formats. As of 2022, the company held an almost 20% market share of the global 2M tonnes harvested, more than double that of the second player (SalMar). It operates in more than 70 countries and employs 11,500 people. Mowi is organized in three business areas:

Sales & Marketing includes secondary processing, value added operations and the sales & delivery of products. Operational EBIT in 2022 was 112M for ‘Consumer Products’ and 61.1M for ‘Markets’. Expanding this segment is part of Mowi’s long-term strategy of focusing on building the company’s brand value.

“The MOWI brand continued its expansion in existing markets in 2022 by launching in more brick-and-mortar stores, and also e-commerce which has been a successful channel for the brand. A volume increase of close to 400% from 2021 to 2022 is a testament to the rapid growth we are seeing”

Feed includes feed plants in Norway and Scotland. Production was 515k tonnes for 2022, achieving a 10% 4yr CAGR. Mowi estimates that the current capacity is at 640k tonnes. In terms of operational EBITDA (the measure the company focuses on) generated, feed generated an inflow of 47M EUR, up from 34.5M in 2021. Mowi believes there’s room for cost improvement and, being feed the most important input for salmon production, companies that offer high quality feed enjoy decent levels of pricing power.

Farming encompasses farming operations, some primary processing and filleting activities in seven countries. Harvest volume was 464k tonnes for 2022 with 63% of the total coming from Norway, and the remaining 37%, from 6 other countries. The five-year CAGR for harvest volume stands at 5.2% (industry CAGR was 4.1%) and operational EBIT totaled 817M. Management mentions that Norway’s farming unit is at the top of license’s utilization and production efficiency, a byproduct of good operational performance. The plan to continue fueling farming is to aim for producing more and larger smolt, and to exhaust multiple remaining licenses in places like Chile and Canada.

Furthermore, Mowi has been engaging with M&A and plans to continue doing so to expand farming capacity and volume harvesting. Last year, it received approval to acquire 51% of the share of Arctic Fish. This helped them expand their geographical footprint to Iceland. Mowi paid 150-180M euros for the company, which has license permission for 27k tonnes and 4.8k in the application process.

One big thing worth mentioning is that the FCR was at 1.13 in 2017, at 1.14 in 2018 and now is at 1.15.

SalMar

SalMar is a vertically integrated Norwegian salmon producer that was founded in 1991 and is currently the second largest player in the market, with a 7-8% market share. The company has a similar operating structure as Mowi, with an S&M segment that includes secondary processing, and farming.

The biggest difference between both, aside from geographical diversification, is that SalMar does not produce its feed in-house, it relies on other suppliers. However, it ensures that ingredients are certified, and SalMar has ‘dedicated personnel who work with fish feed and its nutritional content’. In contrast to its counterpart, curiously, SalMar’s feed conversion rate improved from 1.21 in 2017 to 1.18 last year.

Management team at this company are undertaking huge initiatives that are transforming how SalMar works altogether. The two most relevant include:

M&A. In January of 2022, Norway Royal Salmon merged with SalmoNor, creating the world’s sixth largest salmon farming company. The deal valued SalmoNor at 900M USD and, between both, they have a capacity to farm 100k tonnes in Norway and 24k tonnes in Iceland.

In November of 2022, SalMar merged with Norway Royal Salmon. Interestingly, the deal was dependent on the prior merger. SalMar had conservatively guided for 277,500 tonnes for FY 23. However, management raised guidance in their capital markets day to 362k of harvest volume expected in 2023, with 300k being in Norway.

Offshore farming. In 2018, SalMar put in place the first offshore farming facility in the world. Management believes open ocean farming is crucial for continuous development and supply growth. Furthermore, it could open up new areas for production and verticals for innovation.

In 2021, the company partnered with Aker and created SalMar Aker Ocean, a new joint business completely focused on being a pioneer and developing offshore farming. The ambition is for it to become a global offshore aquaculture company with harvest volume of 150k tonnes. SalMar owns two thirds of the venture.

SalMar, according to their CMD, has a harvest capacity of 350k tonnes and 135k tonnes for VAP as of today. As Utilization and efficiency improves, capacity within facilities would grow to 420k tonnes of yearly harvest volume and 165k tonnes of VAP.

Bakkafrost

Bakkafrost was founded in 1968 by two brothers, named Hans and Róland Jacobsen. In 1971, their third brother, Martin, joined them in the enterprise. The company slowly started to build their farming facilities and is now being led by Regin Jacobsen, who is the son of Hans and has been CEO since 1989. Curiously, Martin’s son, Hogni Dahl Jacobsen, joined the company and has served as CFO since 2019. An interesting fact is that Regin owns 7.9% of Bakkafrost while his mother, wife of Hans, owns 7.8%.

Bakkafrost is a vertically integrated salmon producer with licenses in the Faroe Islands, where they harvest around 70% of volume. In 2019, they acquired a Scottish company that now does the remaining 30% of harvest volume. The thesis for this M&A was to turn around the Scottish business, as it was operating at very low efficiency. Part of Bakkafrost’s strategy is to engage with opportunistic M&A of these characteristics. They had also done this in 2016, when they acquired a small company with licenses in the southern part of the Faroe. Management’s intention is to replicate the business model they have for their main operations in these other facilities, and results seem to be pointing in the right direction.

What uniquely sets Bakkafrost apart from its competition is their completely integrated value chain, which they continue to enhance (ie. Acquisition in Jan of 2022). The company’s control of the entire farming, processing, VAP, and sales, allows it to attack all cost buckets possible and to ensure as high quality salmon as possible. The step of the chain where this is most noticeable is in their feed production. Due partly to Bakkafrost’s “rich access to marine raw material from the waters surrounding the Faroe Islands, Bakkafrost is uniquely positioned to maintain a substantially higher marine inclusion in the salmon feed”, which translates into one of the lowest feed conversion rates (1.03 as of 2022). Given the fact that feed represents approx. 40% of salmon’s production cost, it’s a crucial element to control. Furthermore, their complete control of the value chain puts them in a good position to engage with long-term contracts, ensuring delivery and quality.

With specific regards to salmon, management’s strategy moving forward revolves around the smolt’s size. Previously, the production process intended for smolt to grow from 100 to 250 grams and then release them to the sea. However, salmon are generally farmed at 4-5-6kg, for which almost two years were required for this growth to happen. The problem is that “two thirds of mortality occur in the second year at sea”. Consequently, reducing the time salmon is in seawater dramatically reduces costs, and this is what the ‘large smolt strategy’ gets to resolve. It will reduce time at sea to 12-13 months. The company has been growing it smolt successfully before releasing it to the sea and the target, 500gr smolt would be released in Q3 of 2023.

To this last point, the increased smolt size, combined with the Faroe Island’s natural peculiarity, also helps the company achieve higher kg per salmon harvested. And, due to the lack of supply at this high end of salmon weighting, higher kg salmon enjoy a premium in prices.

Recent tax implementation

After a period of a relatively stable regulatory environment, Norway’s government proposed a huge new tax for salmon producing companies in September of 2022. The foundation for such proposal derives from salmon producers’ apparent “high returns for the low risk they incur in”. Initially, the tax rate was intended to increase to around 60%, from the 22% companies were charged before. After an overwhelming consensual negative from the markets and salmon producers, warning against the measure, the following was agreed in May of this year:

“The Norwegian Government has secured a majority in the Norwegian Parliament to adopt a resource tax on the salmon farming industry of 25 percent on values created in the ocean phase of the salmon production cycle. This is significantly better than the original proposal of 40 percent,” said Grieg Seafood in a statement.

There will for sure be impacts on capital returns and companies’ expansion plans moving forward. However, it is unclear the degree at which salmon producers will suffer from a financial standpoint. The only clear thing is that Norway should turn much less profitable and that the industry itself might face some uncertainty clouds in the short run.

This tax mostly affects SalMar, which derives a large portion of its revenue from Norway, but also hurts Mowi and adds uncertainty to Bakkafrost’s operations in the Faroe Islands. The latter, in parallel to Norway’s government, announced a tax of its own last year. This new tax went into effect in August of 2023 and will be somewhat variable. The tax rate would go up to 20%, depending on the price of the salmon harvested, compared to its index price.

Conclusion

These are three seemingly similar companies, but they drastically differ in the strategies they pursue. On the one hand, Mowi is the largest player with the most diversified operations, which should continue to be the case moving forward. However, things like the FCR’s trend might show inefficiency and perhaps even the condemn of scale.

On the other hand, the company that could potentially offer the best results, though with the highest risk as well, is SalMar. If the company gets to correctly integrate the recent acquisition and successfully develops and scales their offshore operations, potential is immense. But again, integration risk is very high and so is scaling new and mostly unknown mechanisms. In addition to this, considering the heavy tax implementation, it is unclear how it will play out.

Finally, Bakkafrost seems to be the best company on a risk-adjusted basis. Upside potential is very high and I’m inclined to suspect that the company has high chances of achieving its guidance for 2028 (+80% harvest volume from 2022’s). Management has already proven it is capable of acquiring-and-optimizing, increasing smolt size, improving feed recipe and increasing survival rates.

Personal Commentary

Fascinating industry. It seems like an authentic incubator for long-term compounders. Hope you enjoyed the industry breakdown and got some ideas.

Contact: giulianomana@0to1stockmarket.com

Disclaimer: This is not financial advice and should not be taken as such