Honestly, I’m stunned I’m writing this. I did my research on Zoetis during June, July and August, and my conclusion seemed, funnily, conclusive. My suspicion was that Zoetis was as close to being a truly durable company as possible. Even though the object of this article does not claim otherwise, it does indeed reveal something I completely overlooked. My conclusion was ultimately drawn from the following:

The animal health care industry is full of small markets. Most products’ addressable market ranges from 100k-1M, making them truly unappealing for competitors.

There is no company that’s solely focused on generic competition.

Competitors take a jointly (not declared as such) rationale approach towards prices. Knowing these products require certain margins for the rest of the business to be funded, they do not draw them down to 0 profit.

There’s strong brand loyalty from buyers (vets, livestock farmers, some distributors and consumers for companion animal products).

The three points just raised contribute to companies losing, on average, around 40% of revenue from 1-5 years after patents expire, compared to 80-90% in human health.

Unlike human health, an extensive sales force is required to reach most parts of the globe, due to the direct treatment with vets and some distributors.

FDA processes are unbelievably tedious. Several resources and energy have to be deployed to go through one.

Tens of millions of dollars have to be destined to R&D for developing a product.

Building fabs costs hundreds of millions of dollars, if not more. If a company doesn’t count with manufacturing capacity, renting it is highly costly and does not guarantee quality.

The list goes on. In any case, the animal health industry, in terms of fundamentals, is as close as I have seen for incubating truly long-term compounders. However, note that the angle from which I’m analyzing the matter is derived from the perspective of competition on drug development and distribution.

What I have missed is that, although with no extra terminal risk than initially thought, the market can be reoriented. Distribution channels can change for the better, from the perspective of customers. Furthermore, efficiency and disruptive innovation could be developed from the outside and brought into the ecosystem. The latter would invariably either increase efficiency of resource employment, leading customers to spend less money on buying medications, re-think how the supply chain works, or simply change how the last step of the journey takes place, perhaps removing counterparties that fail to adapt to new systems.

Before going into the products whose impact I’ll try to analyze, some pertinent background on how this process works.

Eli Lilly vs Novo Nordisk

Known by many, these are two of the largest pharmaceutical companies in the world, with market capitalization in excess of a couple hundred billion dollars. Both of them have yielded stupendous results from the development and distribution of insulin, in whichever method applied, for the treatment of diabetes. However, what is not well known is the origin of their dispute.

Around a hundred years ago, Eli Lilly’s scientists discovered insulin, a substance that was extracted from animals’ pancreases, mainly those from slaughterhouses. Insulin’s efficacy and consistency is reflected in the purity of the drug. The higher the purity, the better for the patient.

At the beginning, the purity with which insulin could be produced was around 10%. The company became the only distributor of the medicine, a monopoly Eli Lilly enjoyed for several decades. Annoyingly, the method of application was with subcutaneous injections. Patients needed to recur to syringes and receive their doses daily, on average.

Up from the 1920s, all of Eli Lilly’s efforts were placed on increasing the insulin’s purity, for obvious reasons. Scientists iterated their way through pancreatic extractions and, as decades went by, they continuously figured out how to increase purity. Noticeably, each time a new medicine hit the market, with higher degrees of purity, customers paid a premium for the product.

In the 1970s, the drug had reached very high levels of purity, at around 80-90%. Lilly had seen over and over again that, every time they increased insulin’s purity, people were willing to spend more on the medicine. Logically, management arrived to the conclusion that they needed to get it to 100%. To that end, the team invested 1 billion dollars and the results were spectacular. A new method of producing insulin emerged, which made the drug hit 99% in purity. Excited, Eli Lilly takes the new medicine (Humulin) to market and plans on charging a 25% premium. Demand didn’t come.

In parallel, Novo Nordisk, a much lower scale insulin developer, was working on a novel technology, the NovoPen. The latter pioneered a new method of application. Pens are prefilled with insulin, removing the need for measuring and drawing it up from a vial, hence also providing precise dosing, they are more discrete, and the application is more comfortable. Additionally, it essentially brought down the time required per doses from 1-2 minutes to less than ten seconds.

Novo Nordisk took the NovoPen to market and decided to charge a 30% premium for it. I believe the drug’s purity was the same 80-90% as before. Fascinatingly, and in contrast to Eli Lilly’s new product, the market did pay a premium for Novo’s pen.

What happened here?

The Base for Competition Changes

Products are created with a purpose in mind, a job to do. The successful doing of the job is measured in what seems like its ‘intrinsic measurement of performance’, insulin’s purity in this case. That’s the performance customers pay for. It is in companies best interest to improve the product, measured in such dimension, so that customers keep buying from them and paying more.

However, there is a point after which customers do not receive added value for improvements in such a measure. Therefore, they are not willing to pay a premium for it. In those cases, Clayton would say that “the sustaining technologies done to the established product severely overshot customers capability of utilizing such performance”. When this phenomenon occurs, there is room for competition in new dimensions, which invariably provides a window for disruptors.

After the general public is saturated of the initial measurement of performance, they start valuing and paying a premium for other things. In Christensen’s view, the archetypical jumps would lead to competition on functionality, reliability and convenience. Notice that there is a line that determines what the market needs. After it gets fulfilled in a dimension, the competition jumps to another one. Once all of them are satisfied and perfected for the client, the only competition there is to be done is on price.

VetKiosk: Bringing Efficiency to a Giant and Ancient Industry

Agriculture is the practice of, essentially, leveraging natural resources and animals to produce food and relevant material for human subsistence. It emerged around twelve thousand years ago around the globe, independently. Encompassed within it we find, on a broad basis, cultivating the soil and farming animals. Regarding both, it’s on the latter where I want to double-click.

A large portion of animals, ranging from cows to pigs and chicken, are exclusively raised with the purpose of supplying food to humankind. The end goal is as ancient as agriculture itself. Naturally, a farmer’s intention is to extract as much food from individual animals as possible. Efficiency, measured in how much weight an animal gains per kilogram of feed they’re given, is desired.

Historically, most livestock grazed on grasses, leaves, shrubs, legumes and other wild vegetation, mostly labeled as forage. As time went by, humans noticed they could improve the output of cattle by altering the natural process of their feeding. Occasional supplemental feeding was being implemented in the form of grain and straw.

Up to the Middle Ages, the recipe for farming animals stayed fairly stable. However, in the 1300s-1500s, farmers began placing more emphasis on making their practices more efficient. To that end, diets went through several changes. For instance, animals started being more voluntarily fed by humans. Grain crops like oats and barley were cultivated with this specific purpose in mind. At the same time, efforts were made on refining feeding methods. Tools such as scythes and above-the-ground granaries were developed to make the harvesting and storage process easier and more efficient.

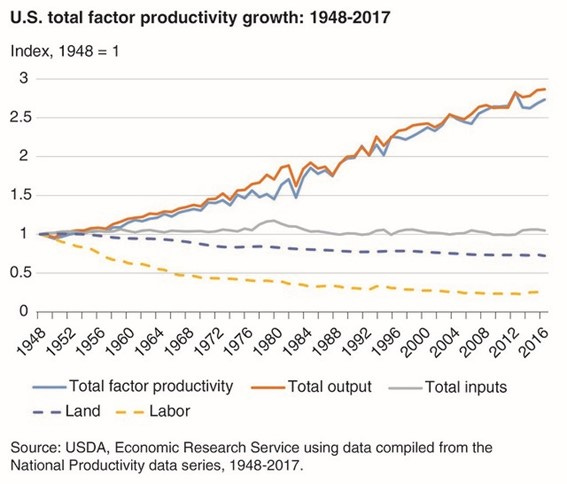

The industrial revolution kicked off a season of wealth creation, bringing large productivity and efficiency gains. Excess capital, after being deployed in technological innovation, found its way to agriculture. Harvesters, cotton pickers, tractors, developed and manufactured by companies like John Deere, caused a pronounced increase in agricultural productivity, even considering the fact that labor and land usage declined.

Note: older data seems unreliable and bear in mind this is a 12,000-year-old industry.

Inefficiencies in Animal Feeding

Most sustaining and disruptive technologies were made with regards to either the food animals consume, or the tools with which humans harvest crops and work the land. To this date, little to no innovation has occurred in the methodology employed for feeding animals. Typically, animals graze on grass and are fed special feed for their correct growth. The problem with the latter is that the system utilized for feeding is incredibly inefficient, resembling processes, as it should, from the past millennia.

Feed is placed in recipients that lie on the floor and, in this case, cattle wander around, occasionally turning themselves to the vessels for food. Several issues arise from such a mechanism:

Cows monopolize food. Since the recipient does not discriminate among animals, the distribution of fodder is not equal. Some cows eat excessively more than they should, taking from others that should consume more. This is a two-sided problem for the farmer.

Depending on cattle’s age, stage of production, type of production, nutritional needs and palatability, the amount, type and quality of feed they should be given. The current system does not allow for a proper information registry record, making this an impossibility.

The feeding must be somewhat monitored by people because of the aforementioned themes. This implies high overhead expenses.

Ultimately, all of these translate into great losses for farmers. It is estimated that 1 out of 4 bags of feed are lost during the feeding process. Moreover, considering that feed is the most important input for livestock production, being around 50-60% of the cost, this is completely undesirable.

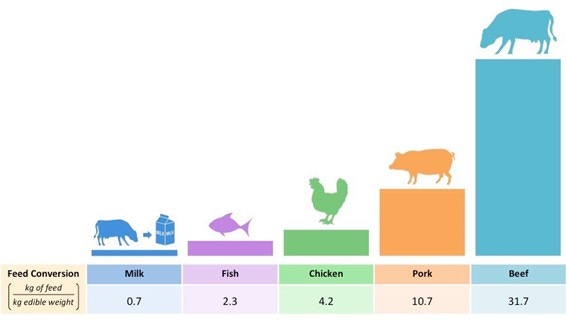

The metric that measures how efficient farming is being done is called Feed Conversion Ratio (FCR). It “measures the efficiency with which the bodies of livestock convert animal feed into the desired output”, kilograms of meat in this case. The lower the FCR, the less feed it takes to increase the animal’s weight.

Even though there is a genetic element to protein retention, I suspect that the mentioned issues are negatively impacting the equilibrium feed conversion ratio. I’d define the latter as the FCR in absence of inefficiencies.

“Byproducts and crop residues comprise less than 1/4 of animal feed used globally. The vast majority is either taken from pasture or grown explicitly for animal feed. Growing crops for farmed animals consumes more than 1/3 of global crop production, yet only 12 percent of those calories then become human food.“

VetKiosk

VetKiosk is an artifact that is meant to replace the current system of animal feeding, which could be seen as an “intelligent recipient”. Farmers could deposit feed into this machine and it would then deliver the food to animals. VetKiosk would, initially with physical elements like collars, but then genetically, discriminate between different animals and supplying only the amount and type of feed specified by the farmer, who would indicate to VetKiosk’s staff the animals’ specific needs.

VetKiosk would remove the need for human monitoring by being consistently working, hence reducing overhead expenses. Furthermore, it would turn cows’ intentions to monopolize feed an impossibility. At the same time, because of its programmable nature, VetKiosk allows for a proper registry record, which helps increase the overall diet’s plan quality.

Room for Large-Scale Impact

Economic activities are only developed when their expected value is positive. The higher the costs associated with different endeavors, the lower the likelihood of them being executed. Given how inefficient animal feeding is, it’s reasonable for the task to be realized less than it could or should, and more so considering livestock’s production environmental impact.

Not making the activity economically rewarding could prove detrimental to people’s lives, from a broad perspective. Taking this even further, it could be the case that current methodologies are insufficient, causing an imbalance between feed supply and demand. Ethiopia has been lately struggling partly due to this.

“Shortage of feed is one of the major constraints that limit cattle production in Ethiopia. This available animal feed satisfies only 63% of demand at a national level.” Paper

To sustainably expand livestock production, it is feed what needs to be carefully analyzed, since it gets to represent 50-60% of total production costs. If we invert the authors’ claim, we arrive at the conclusion that it is not a shortage of feed, or not entirely, what’s causing supply to fall short of demand. It could well be the case that, if feed was administered more efficiently, the gap could be filled.

In Ethiopia, livestock production represents 12-16 percent of GDP. Something similar occurs with countries that have been historically focused on agriculture, like Brazil and Australia. Understandably, given the vast sum of capital destined towards livestock production, losses that occur due to inefficiency that could be mitigated are estimated in the multiple billions of dollars only in Latin America, the continent where VetKiosk is from. This is capital that could be freed to pursue other economic activities or even utilized to increase production, making food more accessible to mankind.

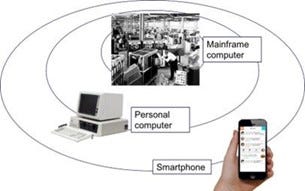

How Industries Evolve

Clayton Christensen thought industries are composed of concentric circles, with outer circles encompassing inner ones. Each circle represents the purchasing power and skill that’s needed to buy and operate a product. Industries begin in the inner circle, serving only customers with money and high technical capabilities. Disruption is the process by which things are made simpler and more accessible. It is disruption’s role to bring new technologies, which are initially complex and expensive, to massive consumption. A good example is what happened with the computing industry.

It first began in the 60s with the emergence of mainframe computers. These costed over a million dollars to manufacture, were sold at 2M dollars and were immensely complex to operate. Consequently, only a handful of companies could have one. The first wave of disruption was minicomputers, which brought down the price to 200k and complexity was reduced, leading to an increase in consumption. Then personal computers arrived, bringing down the price to two thousand dollars and the skill barrier to a point where a great deal of people could operate one. Finally, smartphones came at a cost of 500 dollars and high ease of use, allowing almost the completeness of population to utilize one. What the process of disruption did was to make computing power more and more accessible.

VetKiosk is Disruptive by Definition

There are two other types of technologies. Sustaining technologies are marginal improvements to products, those that increase their performance, however measured. Efficiency technologies bring down the cost of manufacturing a product. The former is done for high-tier existing clients and can be sold for better profit, while the latter improves the company’s profit margin by optimizing the manufacturing process.

On the other hand, disruptive technologies necessarily either begin at the bottom end of a market or aim for non-consumption. Non consumption means it targets people that weren’t customers previously, mostly because of the purchase price or the product’s complexity. I suspect that VetKiosk would fit this second description.

The estimated 25-30% savings the product generates should allow for two things:

Farmers that didn’t engage with animal husbandry because of high-quality feed’s cost now see their baseline costs reduced. VetKiosk allows for the utilization of high-quality feed at a much lower overall cost, because of the efficiency gains.

Farmers that already raised animals now will be able to either free capital to pursue other endeavors or increase production by an expected lower FCR.

My hypothesis is that a large genetic component is embedded in FCR, but that this will nonetheless diminish. In any case, an equal investment in feed would now allow for the feeding of more animals, perhaps up to the 25%.

I believe both things help make the case for VetKiosk to be disruptive. The product will bring the cost barrier of the whole industry dramatically down. In the absence of something like an integrated manufacturer, as in the steel industry, there’s no real player to displace. However, my sense is that farmers that do not adopt this new mechanism will succumb to the price war because of VetKiosk-adopters 25-30% lower costs in the most important element of animal farming.

Lastly, closely monitoring VetKiosk’s selling price will be what would help make a final judgment. A too-high cost and, therefore, selling price, would imply for only high tier clients to acquire a VetKiosk and displace smaller competitors. On the other hand, if the cost of manufacturing and selling price are low enough, I suspect this technology will turn non-consumption into consumption. Nevertheless, the latter would need to operate at the sufficient scale so as to cover for this extra initial investment.

What Does This Mean for Zoetis?

Zoetis sells medicated feed additives to farmers and veterinarians who could then distribute them. If the estimated losses due to the archaic system in place are accurate, Zoetis’ 360M generated through this segment are an overestimate of its demand’s actual needs. Savings would translate into much less feed needed to be bought to generate the same output for farmers. Nevertheless, Zoetis’ losses due to farmers’ efficiency gains might get eclipsed by farming becoming more economically rewarding and hence attracting more capital.

However, the story doesn’t end here, as we now need to turn to FeedVax, a product that goes hand-in-hand with the VetKiosk. I will break it down, along my thoughts, in a second part of this series.

Personal Commentary

This was a fascinating article to write. The theory of disruption is a framework through which we can analyze technologies. I think it is superbly powerful and I am trying my best to master its usage. Hope you enjoyed the article and I’ll try to have the second part for the coming weeks!

Contact: Giulianomana@0to1stockmarket.com

Very nice read! I know this article is dated. But do you think $ZTS has reduced their risk in this area by selling off this feed additive business?

I also try to look at things that can break my investment thesis, but this is on another level. Thanks for writing this!