I have just finished editing this article, literally two minutes ago. It was the most difficult piece I’ve ever put together. I sincerely hope you enjoy it and/or find it useful, and encourage you to subscribe after a skim!

I understand it is a long read, if you prefer the PDF version, here’s it:

Prologue

This is a terrifying article to write. It is not until you start writing about something that you find out how cluelessly you were operating and how weakly connected your ideas were. However, I’ll be reporting and writing about the fund’s (let’s call it that way) performance when the semester ends (next week). Therefore, I considered it appropriate to extensively share what I believe composes my investment philosophy. But before doing so, some thoughts and considerations.

Things change

The world, life, and the markets, are dynamic. Things are constantly changing and information flowing. In a similar manner, knowledge is continuously being acquired as books and thinking go by. Singular new pieces of ‘wisdom’ make me re-think my approach and with good reason, new information threatens and interrogates previously conceived ideas. Consequently, when I learn something, I simply change my mind, adapting it to this new knowledge. Even if seen as hypocrisy, I find being able to change one’s mind a sign of strength. It is one of the most difficult things to do, in my experience. This is nothing more than a notice. I might and will change my mind. I don’t intend this write-up to be eternally associated with my investment philosophy nor for it to represent an absolute truth. It is only mine and as of today.

How to add value

I see this, combined with the performance update, as my first ‘shareholder letter’, not in the explicit sense, but in a symbolic one. From what I’ve seen, shareholder letters are not only about sharing how a partnership or fund performed during a determined period, but also about sharing management’s thoughts, ideas, philosophy and even information they consider interesting. My intention is for this long-form article to include all of this, trying to emulate an authentic shareholder letter. However, I noticed (among my small repertoire of reads) a huge problem fund managers face when writing these. It is getting increasingly difficult to add value.

After reading Buffett Letters, I thought they were fantastic. However, after reading other managers letters, I realized how absurdly wonderful Buffett writings are. Why would you read me when you can simply grab whichever of Warren’s 60 letters or so and find a wealth more of wisdom and clarity. I don’t have a magical answer to this issue. I’m trying to figure things out and hope to help you do so as well in the process.

I see repetition, everywhere. It has gotten to a point where I can’t really tell who is thinking for themselves, which is the only way to escape competition. For this reason, many articles (mine as well), books, are only cheap copies of the already great ones. How to add value then? I do not have an answer. However, even though I will include quotes, charts and extracts from many investors, I will try to deliberately explore what I think to be true and best represents my investment philosophy. In most cases, it will be a matter of taking other people’s ideas and pushing them a bit further.

Reinventing the wheel

Humanity has been around for a long time. Written history traces back to 3,000 years before Christ. Ever since, and combined with the verbally transmitted ancient stories, we’ve been in charge of keeping a register of our daily lives, as well as the ideas we may have had. This way, knowledge is taught, reproduced and, at a final stage, applied. But, furthermore, it compounds.

You can save a lot of time by learning from history. You do not have to take the shot to learn how to avoid being in the crossfire. I think this is where the concept of “there’s no need to reinvent the wheel” comes from. Our predecessors worked to make the wheel happen, took the time to think how it could look and arrange its physical construction. To build a car, you do not need to reinvent the wheel, you can just leverage its invention and use it, saving time.

This is contradictory with what I generally profess. I give a lot of importance to the act of thinking and, using what others have thought and built, seems rationally illogical. Nevertheless, I also believe in efficiency and risk/reward. Reinventing the wheel could bring mind-blowing results (look at Jim Simons), but doing so not only requires an absurd amount of time, but also talent, which is also ridiculously scarce. Moreover, the reward for succeeding does not show until the product is successfully invented, meaning one has to endure the process with no guarantee no tangible signal of victory. From a psychological perspective, this might be one of the toughest activities to perform. It’s not about conviction, it may be a matter of insensibility. One has to be willing to be the stupidest person alive for as long as needed until you ‘suddenly’ become the smartest person alive, without ever knowing that time will come. It probably takes some sort of sociopathic personality to be capable of dealing with this.

I try to stay truthful to myself. I don’t think I belong to that genius 0.001%, but I do think I’m capable of taking what the investment community knows and building a strategy that works. Maybe even arranging supply in some way that the result is unique. There is some genius in that as well, as ASML showed during the 80s.

The reasoning behind the prologue

We don’t take most things seriously. In ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow’, the author explains what he thinks composes our brain from a structural and pragmatic perspective. He differentiates between two states, or systems, in which it operates:

System one is the default. It is like being on autopilot. It’s the one that fills in theoretical and conceptual gaps with previous beliefs to not succumb to a constant state of heavy thinking, which could be unbearable. System one, therefore, is the quick reactor to circumstances, providing us almost instantaneous answers based on intuition and past experiences.

System two is the one we recur to when we need to solve complex problems. It is the one that is capable of thinking rationally, logically and elaborating complicated hypothesis, conjectures, and solutions.

The issue with our brain’s functionality is that system two demands a lot of computing power and resources, making it extremely effortful to utilize and, therefore, undesirable by our human condition. If I don’t have this incorrectly, we are genetically and biologically built to go with the lowest-effort activity. Consequently, it is not normal for us to want to access system two and voluntarily activate its thinking process.

I believe that, even though it takes some effort, we can consciously access system two if we take things seriously and even more so if we make ourselves accountable to others. Both things force us to try our best, nobody wants to look bad. Not taking it seriously is easy. I could simply put 3 charts showing what research suggests and end the article with, probably, both of us satisfied. However, my intention is to really go over what the title states.

By taking this write up seriously, with all that it means, I’m forcing my system two to make its appearance and deploy all mental resources. This way, I will try for you to leave this article knowing in a concise yet accurate (as much as possible) manner how I think about things, why I do so and, more importantly, what guides my investment principles.

It’s okay to not know it all

This is something one would not expect to read from a portfolio manager. However, even though I’m young by common standards, I believe I have dedicated a decent amount of time to exploring single verticals of knowledge. Once I saw that ignorance only increased as I read, I realized it is impossible to know everything. This is not a novel discovery, but a personally profound one.

I spent probably a couple hundred hours researching only Microsoft. Before beginning, I expected to be an expert at this point. Not out of vanity, but common reason. Time has proven me wrong, something I’m quite used to. Even though I have some basic understanding of practically everything regarding Microsoft, every time someone speaks about a particular thing, I rarely know what he’s talking about. Recent example from a conversation I had with a guy that works at Microsoft, Azure particularly:

Friend: Did you know that Microsoft Azure has its sales cycle split in two parts?

Me (ashamed): I have literally no idea what you are talking about, how so?

Friend: Well, Microsoft has its authentic sales team that is in charge of convincing potential customers of buying Azure. But it also has the team that helps singularly visualize the implementation of the technology in the customer’s respective business.

I am fortunately not afraid of asking questions, even the dumbest ones. This answer sounds completely logic, if you think about it, but I hadn’t. I could have simply said “yeah, of course I know” and changed the subject. The problem is I wouldn’t have known something about Microsoft. If being a fool for a minute helps me better understand a business, I’ll take that trade off every day of the week. Moreover, if I have to read 1,000 books to get to a long-durable and working strategy, I’ll simply do it.

Probabilities

We are not biologically capable of perceiving reality. Everything we see is previously filtered by our body and mind. Even language is an absurdly complex thing. Speaking with precision is fundamental for the counterpart’s understanding. Most words have an innumerable number of connotations and phrases even more. We barely understand things and that’s okay, it’s our mind’s way to not overload itself. If you don’t believe me, try simply defining a word.

The only certain thing about the future is that it is uncertain. Understanding this is easy, interiorizing it, not so much. To deal with such complex phenomena, we operate probabilities. Decisions are made based on their probability of success. We are trying to build a long-durable system for making decisions, and probabilities are right at the center of it. Over the long run, when enough simulations have been played out, decisions’ success rate will tend towards the expected value with which they were taken. We aim to make decisions with an expected success rate of at least over 50%. I believe it will continuously improve as time goes by.

Investing is a game with uncertain outcomes, but one in which you can certainly stack odds in your favor.

Thinking, a competitive advantage

We all had the same education, we all read the same books, we all listen to the same investors, and we all have access to the same information. Without diving further into these extremely alike characteristics we all share, differentiation sounds utopian, unachievable. The crowds conform the markets, and doing the same things the crowds do, leads to underperformance. There is no alpha in what everything does, but, as described, it seems impossible to not follow.

After dedicating myself to thinking about this, I think I arrived at a solution. Doing things because others do them signals a lack of thinking. It is impossible to have the same idea and strategy as another person, unless you copied them. Each of us is unique and has infinite singularity. We cannot possibly reach the same conclusions as other people because of our unique life experience and learnings.

Finally, only by exercising thought one can, at least partially, infer what’s the thesis behind a decision. Only by thinking we can determine relevant factors we are considering for decisions. Ultimately, only if we have done this will we be able to ‘know’ if we were right or not. If I’m right and I don’t know why, future decisions will keep being simple coinflips. If I’m wrong and I don’t know why, I cannot improve my process because I won’t know where to look. However, if I’m able to build a universe of relevant factors behind decisions, I can track them moving forward, allowing me to either continue with the process if good, or improve it if wrong.

Last footnote

I never go into details of what I think, usual articles length limit myself. There’s beauty in conciseness, in brevity. I remember myself reading one of Conor’s articles and finding the following quote (I’m paraphrasing):

“I apologize for the length of this letter, I did not have the time to write a shorter one”

That’s brilliance at its peak. A person that is able to break down their ideas into simple and concise sentences is a person that has thought about the subject. If not, the task would be impossible. Achieving brevity and substance is no joke. However, I believe there are occasions in which length is not only necessary, but also useful.

I dedicate my whole day to thinking about these things, about the stock market, companies and philosophy. How could you tell that if I only write 700 words per week? That could make a reader think that the writer only dedicates one or two hours per week to the subject. Furthermore, there is not enough space in Sunday articles for me to transmit all my thoughts.

In the same line, brevity is a double-edged sword. It can well show understanding and brilliance, but it can also show a lack of understanding. It is very easy to get rid of concrete implications with imprecise sentences. For all these reasons, I’m deviating from the usual path. I’ll be expanding accordingly to get closer to a guarantee that arguments, ideas and everything I put on here have been thought about thoroughly.

Investment philosophy

I had to go through an innumerable number of articles/books/podcasts to grasp what the best, in my opinion, approach to investing was. By reading great authors and investors I got to a point where I believed I had found the intersection of ideas and shared concepts where I could be comfortable operating.

There have been a lot of outperformers and with many different styles. It was up to me to get to know myself well enough so that the strategy I followed was one that could bring good results, but also one that wouldn’t collide with my personality. A lot of money has been lost because of people’s lack of knowledge of themselves. It is very common to stick with a plan that goes against one’s nature, but, eventually, nature wins.

A good investing strategy has two ingredients:

Delivers relatively good results

Durability

The funny thing is that only in retrospect will I be able to tell whether I found one or not. One thing history has shown is that playbooks change. Perhaps the result of a dynamic world or because its thinker found better ways to do it. Small improvements seem to be the key when you are not Jim Simons, an outstandingly brilliant person.

The strategy

The strategy is simple, but not easy:

“We want to own good businesses for a long period of time.”

It was not until I read Terry Smith letters that I clearly saw the path to follow. The 3-step playbook he came up with is what we are going to stick with, but with a small tweak in the first step. Terry writes:

“We continue to apply a simple three step investment strategy:

1. Buy good companies

2. Don’t overpay

3. Do nothing”

The only change I made is, instead of “buy”, in the first step, it’s “find”.

Step 1: Find good companies

Before expanding, a concise yet elaborated definition of what I think makes a good business:

Good businesses are those that have high returns on capital, allowing them to capture better reinvestment results than average. They have idiosyncratically good fundamentals. Good businesses are immersed in fundamentally good industries. Good businesses have a shareholder and long-term mindset. They have a management team that knows what to do with money. Good businesses have long and durable competitive advantages.

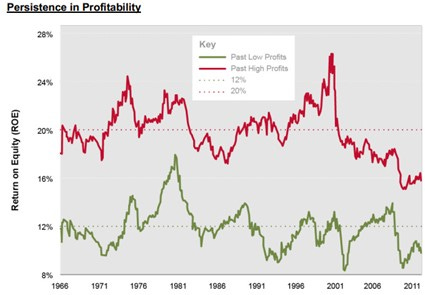

High returns on capital

‘Returns on capital’ have a transparent definition. It’s the rate of return a company can achieve by investing its capital. On most occasions, by reinvesting it in their business. The purpose of reinvestment is to capture a larger piece of their market, capture the market’s secular growth, improve a product, expand margins allowing for further value retention, build a better distribution network, a better supply chain. Consequently, the underlying superior company remains superior and cannot be displaced by competition, at least letting it return more and consistent value to shareholders.

Moreover, it is one of the key elements that signal a strong competitive positioning and determinant for investing results:

“Over the long term, it’s hard for a stock to earn a much better return than the business which underlies it earns. If the business earns 6% on capital over 40 years and you hold it for that 40 years, you’re not going to make much different than a 6% return- even if you originally buy it at a huge discount”

I understand efficiency as one’s ability to achieve the result by employing the least amount of resources possible. High returns on invested capital allow you to achieve more with less. Example:

Company A has a 10% return on invested capital

Company B has a 20% return on invested capital

They both have alike characteristics and belong to the same industry. Let’s imagine they are at 1bn in EBIT and want to grow 50% on X period. To get to 1.5bn, company A would need to invest 5bn dollars. On the other hand, company B would need to invest 2.5bn dollars. Achieving the same result with half the capital allows company B to utilize the remaining capital to reinvest it in the business, enlarging its competitive advantage, or return value to shareholders. Time only makes the discrepancy between the two grow larger and larger.

We want companies with high returns on capital.

Idiosyncratically good fundamentals

Idiosyncrasy is inherent to individuals and businesses as well. It is composed of the characteristics that are unique to these, those that differentiate them from others. In the business world, this idiosyncrasy can be spotted by simply looking at business fundamentals. Even though there’s always uniqueness in context, in physical space and so on, differences between margins or returns on capital among very much alike companies would be inexplainable. There are companies that are simply better than ‘competition’ (no mystery, they do things better).

Business is not only about value creation, but also value retention. A company that earns 10bn dollars and keeps 0 from it, is a valueless company. The amount of value a business is able to retain from the created is an indication of how strong its positioning is. It shows how competitive a market is and, therefore, which of them to avoid. Companies that perdure in time are those that do something unique or in a unique way. It cannot be copied, or at least not easily.

Margins and profitability are what gets the closest to showing how much value is a business able to retain from that created. Moreover, and I have to steal this from Terry, companies with higher margins tend to be more protected from inflation, which can really harm a business.

Transversely, we look for companies that are in a healthy financial state. Financial fragility makes a business future much more uncertain. Being the future utterly unpredictable makes adding another problem to it, unnecessary pain. A company’s balance sheet reflects how well prepared is the company for the future. In some way, it shows how flexible can the business be, and flexibility is something we look for. It is needed to deal with the problems the future will bring. We look for companies with high levels of cash, low levels of debt (or well issued), an intended inventory position and capable of dealing with obligations in the short and long run.

Capital and asset intensity is another important factor to consider. Companies generally stand between a capital light and capital-intensive model. Wherever the business belongs to in the curve, it is crucial for its place to be the correct one. Visa has a capital light and asset light model, because, given its competitive stance, it doesn’t need to spend much capital to maintain it. Moreover, there’s no need for Visa to make itself a heavy asset business so that VisaNet works. On the other end, Microsoft has become a somewhat heavy asset and capital-intensive business because of Azure. In the last twelve months, it spent 26bn in CapEx. The vast majority of this is destined to building datacenters and advancing the existent infrastructure. This is seen as a good move to solidify its position in one of the most promising markets for the next decade and continue grabbing market share.

We want companies with idiosyncratically good fundamentals.

Good industries

We are victims of our context, our environments. As individuals, it is easier to change our environment than to change ourselves. If you want to stop drinking, just stop having beer on your fridge. If you want to start reading, get rid of the tv and put books in places where you usually lay down. In businesses, it is the complete opposite.

Industries are the playfield. The industry you are in determines a large part of your potential returns on capital. It determines a business’ market conditions, how high are the barriers to entry, how many players can there be, the chances of disruption. The industry defines the rate of structural growth and its perdurance. It is easier to grow in an industry that is growing than in an industry that’s contracting. Furthermore, the very nature of industries sets the potential longevity of their growth.

Time is the ultimate judge. It is not easy to stand through time’s tests. As Nietzsche said, what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger, and companies-industries are very well represented by this. An industry that has resisted the appearance of new technologies, widely different economic cycles, is an industry with more chances of resisting what will come.

I cannot leave this part without one of the greatest quotes I’ve ever read on investing:

“A textile company that allocates capital brilliantly within its industry is a remarkable textile company – but not a remarkable business” Buffett, 1985

We want companies that are in fundamentally good industries.

Long term and shareholder-oriented mindset

We invest in people. Companies are nothing more than a group of people dealing with problems. We are looking for people that are the best at dealing with these problems. But, furthermore, we are looking for people that run their business for the long term.

“He who knows where he’s going might not get there. But he who doesn’t know where he’s going will for sure not get there”

If a company doesn’t plan the for long term, there will not be a long term for that business. Moreover, there needs to be compatibility between the investor and managements’ time horizons. Different time horizons motivate drastically different decisions. Investing for the long term needs to be done in a group of people that makes decisions for the long term.

People want to be associated with others that want the best for them. From a shareholder perspective, a company that creates a wealth of value with shareholders’ money, but does not return any of that value to investors nor creates value for them, is a bad investment in the long run. If management does not care about shareholders, the decisions they make will hurt us. Perhaps not out of pure evil, but simply out of not being a relevant variable for them.

We want a long-term and shareholder-oriented mindset

Good capital allocation skills

Money is companies’ blood and oxygen. It is up to nature to manage them accordingly within our bodies, supplying areas where they are needed and keeping the flow constant. If our interior manager doesn’t know what to do with both, we’ll end up in the hospital. In companies, it is the same thing, without such a drastic outcome though.

A management team that doesn’t know what to do with money will condemn a business’ future, independent of how bright it could look like. In the middle of both extremes, a management team that’s not brilliant, but neither stupid, can perpetuate the life of businesses with heavy moats. Finally, a management team that allocates capital correctly will be a key determinant of their future business’ success.

Money is a resource. Being able of utilizing it as well as possible will, as time goes by, destroy any type of competition. It will help a business maintain its competitive position, solidify it and, ultimately, continue grabbing market share. The reason being that capital allocation skills compound over time. From a practical sense, even a 1% difference in ROIC supposes an immense gap between companies over the long run.

The symbolic value of money does not change over time, but its true value does. A management team that understands this will know how to take advantage of different scenarios to create the most value for shareholders. In an easy-money environment and depressed stock market, issuing debt to buy back shares could be a brilliant play. However, doing so in the opposite scenario leads to value destruction. When the market is absurdly optimistic with a company’s stock, raising capital by issuing shares could be a brilliant play. Again, doing so when your business is valued largely below its intrinsic is intensely harmful for shareholders. Good management teams leverage all contexts, raising capital when they can, not when they need to.

We want good capital allocators.

Long-durable competitive advantages

Competition is undesired, it is a benefits-destroyer. Companies that know this focus on protecting themselves from potential intruders. To deal with it, they build intangible or tangible advantages and distinctions, aiming towards complete irreplicability.

A business’ brand is difficult to copy. A company that invents something spending tens of billions in R&D is a company with a monopoly, at least in the near term. A company that has the largest physical distribution network is an impossible company to compete with. A company in which the world’s economy relies is highly unlikely to be rapidly displaced. A business that provides you with recurrent services and has been integrated with your whole ecosystem is difficult to replace. A business that protects itself with bureaucracy is a provider people won’t likely change.

These barriers a company can create to protect its business and the profit it generates, help it perdure in time. They add a bit of certainty to their future, which ends up increasing their chances of remaining alive. Finally, it leaves no room for competition to eat away their lunch.

We want companies with long-durable competitive advantages.

Culture

People are the backbone of any organization. Humans want to be around others they like, with whom they enjoy spending time with, people they admire. We do our best when we are surrounded by the best. This is a crucial aspect and a leading indicator of a business’ future success. If a company has the best people, the remaining best people will want to work with that company. Culture is talent’s beacon.

We want companies with a good culture.

Step 2: Don’t overpay

Returns depend on what you buy and how much you pay for it and, as exposed, investing is about stacking odds in your favor. One way to do it is by paying as cheap as possible for something. Asset prices contain vital information, it tells you what other people think the asset’s value is. However, not always is that value close to the intrinsic one.

“The outcome of buying the right company at the wrong price will be a poor investment decision”

Margin of safety

Because we do not know the future, we have to play our hand as well as possible so that the future has little to no chance of sweeping the floor with us. The price we pay for a business determines the potential downside there might be. If we buy something at 50% of its true intrinsic value, it is very unlikely that, over the long term, the investment performs badly. Conversely, if we buy something way above its intrinsic value, the path of least resistance is downward.

Everything we do is about increasing the margin of safety.

The reality of good businesses

It is very rare in today’s world, where information is massively available, to truly find good businesses at bargain prices. The market is faster than ever in correcting its inefficiencies. Consequently, good businesses are highly priced most of the time. And with good reason, companies that are expected to continue being alive during the next 20-30 years shouldn’t be priced in the same way as one that could go out of business tomorrow.

That’s why I particularly liked the part of, not buying cheap, but not overpaying. Buying cheap supposes that there are and will be chances of doing so. But it rarely happens. Good businesses only occasionally are truly cheaply priced. That’s why we believe paying a fair price for a wonderful company is replicable, scalable and should deliver decent results.

Where it all gets together. Here’s the second part of an early quote from Munger:

“Conversely, if a business earns 18% on capital over 20 or 30 years, even if you pay an expensive looking price, you’ll end up with a fine result”

Patience

In 2004, Nick Sleep wrote about the importance of waiting for a correct enter price. Moreover, he gave a fair argument of why this makes sense. It would be stupid to wait for something that will never happen. While researching, Nick found a particular study that called my attention:

“Over time, this offers [the study] the prospect that any business, indeed all businesses, will be meaningfully mispriced” June 2004

Patience is required and we’ll come back to this point later.

Step 3: Do nothing

Time is a double-edged sword. It can be an investor’s best friend or worst enemy. Curiously, we can control what it ends up being. It is our decisions what makes time tilt towards being our friend or enemy.

Fundamental convergence

The market is made up of people. People that send signals with their buying or selling decisions. The first of the two signals that the underlying asset’s current value is below its intrinsic (as of their respect), while selling, the opposite. A decade of price fluctuations contains an infinite amount of signals, each of them backed by singular reasoning and circumstances.

In the long term, all these signals have to converge towards something. Even nothing is something in this case. Since the intrinsic value of an asset is the expected cashflows it will generate discounted to today, that’s the point of convergence after a sufficient amount of evaluations. It is not a mere casualty that, over the long term, fundamentals and stock prices converge, it is the philosophical aim of this complex artifact. If a company creates and captures more and more value, the company’s value will tend to increase over the long term.

The short term is a different creature. Calculating the true intrinsic value of a business is not easy. In fact, it is impossible. That’s why, partly and over the short term, prices are detached from fundamentals, because there are too little iterations included in it. Therefore (classics are classics for a reason):

“In the short run, the market is a voting machine but in the long run, it is a weighing machine”

In ‘The Wisdom of Crowds’, Michael Mauboussin expanded on this. He included in the research article several examples about how crowds are, on average, wiser than individuals. The classic example is when he speaks about his usual class experiment, in which he fills a jar with candies (or something like that) and asks each person to write how many candies they think are in the jar. Interestingly, individual answers range is enormous, but the average is almost always very close to the real number. The larger the crowd, the more the average answer should tend towards the true value.

We could think of the short term as a small crowd and the long term as an infinite one.

Too much action leads to underperformance

Our condition of humans limits our comprehension and overall capabilities. We are not omniscient. It is almost impossible to make many decisions that are truly well grounded, because we do not have the time nor mental capacity to do it. For this reason, the more we interfere, the more we are splitting our limited resources among decisions. Ultimately, this ends up making for a compendium of many poor decisions, leading to most of them being coinflips, leading to underperformance.

Almost the end

We covered the structure of what my philosophy and investment philosophy is, but there are a few more topics to talk about. I couldn’t encapsulate this in any of the steps, but they are very important for managing a portfolio, for which I have to include them here.

Selling

In a world of linear progression and returns, a world in which companies are permanently fairly valued, selling is pointless. Unfortunately, that is not the real world. Our holding period is theoretically forever, but for pragmatic reasons we have to make some exceptions.

The market works in the form of a pendulum, oscillating from pure fear to euphoria. It is up to portfolio managers to know that and to learn how to take advantage of the two scenarios. We talked about buying and not overpaying. Preferably, the best buying point is the scenario of extreme fear. And logically, the best scenario for selling is extreme euphoria.

When I have a spectacular business that’s being (in my opinion) ridiculously overpriced, it seems not rational to hold such stock. The path of least resistance is downward. As simple as it sounds, it becomes very tricky because we never know when something is ‘ridiculously overpriced’ even though we may have an idea. However, I think that the closer to this extreme we try to operate, the higher the odds of making a correct call.

Since the fund’s inception on January 2022, only two sales of stocks that belong to the optimal portfolio were made:

Nvidia at 275 on the 3rd of April, after a 98% return

Shopify at 63 on the 22nd of May, after a 33% return

Nvidia’s selling proved to be a massive mistake, in the short-term hindsight. There is still chances for price to fluctuate given we are in the short term, but if Nvidia doesn’t revisit lower prices, the decision was wrong. We thought we were close to the extreme in euphoria and we were wrong. That’s why, even when it seems crystal clear, it is not. On the other hand, it is extremely early to tell if Shopify’s selling was correct or not.

Risk

Volatility is not risk, it’s opportunity. It is a risk to see it otherwise. Portfolio managers should be capable of taking advantage of the different scenarios volatility brings, just as CEOs. The only real risk we see is the risk of misanalysis. Because prices and fundamentals converge over the long term, the ‘only’ mistake we can make is misinterpreting a company’s future or paying too much for it. In both cases, it represents a misanalysis.

“Risk is what it’s left after you think you’ve thought about everything”

Portfolio building

Diversification

Diversification is good only when done correctly. To evaluate a portfolio’s diversification one could look at the number of businesses that composes it, the number of business units those have, the client concentration each business has, the different industries the portfolio is exposed to, the economic cycles each company is favored by.

We keep in mind two truths regarding diversification:

Because we do not know the future, we cannot put all eggs in one basket

The more companies you include in a portfolio means your attention and knowledge is splitted among more companies

Considering both, we are looking for the number of companies that check all boxes, but does not dilute single knowledge and attention to a detrimental point.

Destination

Destination is an important factor we consider for diversification. Positions are sized according to the future prospects we believe they have and the potential downside as well. Nick articulated it magnifically:

“The high weighting makes sense given our understanding of the destination of the business and the probability of reaching that destination” June 2007

Capital allocation and the optimal portfolio

We aim for the optimal portfolio to be made up of the best businesses in the world and for each of them to have the allocation we believe best suites their prospects and downside. However, reality strikes again. This is not a world in which companies are permanently fairly valued. Consequently, capital allocation will be in accordance with availability factors. Even though the portfolio will tend towards the optimal, we will not ignore if a great business is massively mispriced.

Epilogue and personal commentary

I rarely run out of words, but I might just have. I genuinely hope that you enjoyed the write-up or at least found it useful. This was a crucial document for me to write. It was definitely a terrifying task.

Contact: tute.mana@gmail.com

LinkedIn: Giuliano Mana

Excellent work. After reading this, I also see how important of an exercise it is to write out our investment philosophy. Looking forward to next year's annual letter!

aporta mucho valor tratar de comprender el mercado algo muy dificil pero con buenos analisis y objetividad saludos y gracias