Michael Mauboussin’s repertoire of research articles have proven to be a delightful read. They helped me expand information of specific financial concepts and ratios, leading to a better holistic understanding of how financial statements work altogether.

Moreover, he very clearly lays out what theory says and how he thinks it’s not in accordance with reality. Funnily, I noticed that every time he can, Michael gives earnings/EPS/PE a beating. In today’s article, we will explore why these financial metrics are extremely misleading and fundamentally flawed.

Where accountancy went wrong

Bookkeeping and accounting, from a broad sense, traces back to a couple of thousands years ago to Ancient Mesopotamia. The purpose of the developed system was to keep track of goods, expenditures and trades. A bit further in time, it evolved and also helped keep a record of inhabitant’s obligations to the ‘state’.

Contemporaneous accounting, which encompasses the current structural delimitations, was introduced in the Medici’s bank by Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici. In the late 1400s, Luca Pacioli, The Father of Accounting, further elaborated in his book what would the double-entry bookkeeping consist of, alongside thorough descriptions of arithmetic and algebra.

Fast forward 500 years and the system has been barely modified. At its core, the purpose of bookkeeping was to keep track of capital and physical assets. During the nineteenth and twentieth century this worked magnificently, as output was almost directly linked to labor and machinery. However, the past 50 years have been characterized by the emergence of new economy companies.

Mauboussin distinguishes new from old economy business by essentially observing where they derive growth from. Traditional companies need to invest in physical assets, which they capitalize on the balance sheet, to grow. On the other hand, new economy companies are reliant on knowledge, intellectual capital, intellectual property and, therefore, intangible assets. This makes the whole accounting system somewhat useless when trying to infer these companies’ value. I will try to go over how to fill this gap in the future, but there’s something more pragmatic that needs to be addressed.

The problem with earnings

In “The Trouble with Earnings and P/E Multiples”, written in 2001, Michael explains that expectations investing is “to correctly anticipate changes in the market’s implied expectations for a company’s long-term cash flows”. However, most investors get caught up in short-term earnings analysis. Hence it was important for him to shed some light on the following:

How do we know the market is long-term oriented?

Why do investors focus on earnings?

Why are earnings unreliably linked to stock prices?

Before making a case for something, I find it crucial to analyze whether the case itself is well grounded or not. It would not be wise to spend time playing a long-term game when it should be otherwise. Against the popular view, the stock market takes a long-term view when valuing businesses. This conclusion can be reached in two straightforward ways:

Analyze how much of the company’s value is attributable to short term (3-5) years of dividends. “As it turns out, we can only attribute about ten-fifteen percent.. to expected dividends over the next five years”.

Analyze how many future cash flows it takes to justify today’s price. “We find that the market-implied forecast period for US stocks clusters between ten and fifteen years”.

The reason why it is much more common to think the market has a short-term view is due to how the investment community is organized. Firstly, it seems that consensus suggest that EPS are the metric with which corporate performance must be measured. Moreover, financial media companies have done nothing but harm in this regard, as they have consistently emphasized EPS growth and PE multiples. This gets further aggravated by the alleged stock prices’ reaction to quarterly EPS announcements and portfolio managers’ focus on quarterly performance.

To answer the last question, I’ll also utilize Michael’s article called “Counting What Counts”, published in February of 2000.

Earnings vs cash flow

The fundamental problem with earnings, which acts as a foundation for other financial metrics like EPS/PE/PEG/ROE/ROA, is that it was never intended for them to represent cash flow. And it is the latter what has empirically explained price action over long periods of time.

Earnings can materially differ between two different companies with the same cash flow due to the flexibility the GAAP accounting method offers. Some examples:

Revenue recognition. It is becoming increasingly difficult to report revenue when it’s realized and earned. Some SaaS companies, for instance, defer part of the revenue generated to cover future potential costs associated with them.

Merger accounting. I think this is no longer the case, but it was until the year 2000 at least, and helps make the point. When a merger occurred, companies could structure the deal as a “purchase” or “pooling”. Purchase accounting generated goodwill and poolings did not. Amortization (non-cash expense) of goodwill will affect earnings, but not cash flow. Hence why, depending on how the company decided to structure a deal, the earnings it would report.

Inventory valuation method. Depending on the context and method the company employs, the reported earnings and even cash flows the company has.

Deferred taxes. “Varying depreciation methods can create a wide difference between a company’s actual tax bill and the provision for income taxes that it shows on the income statement”.

“Not surprisingly, about 20% of the S&P 500 companies in a typical quarter beat the consensus earnings estimate by just 1 penny”

The most dangerous metric, the P/E multiple

We went over how the method companies utilize to report their earnings affect earnings themselves, but not necessarily cash flows. This foundation should already be enough to understand why the P/E is intrinsically flawed, as earnings are what the P/E is based on. But it is even worse. The P/E multiple is utilized to get an estimate of value, yet the following quote clearly lays down why it is impossible for it to be useful in such regard:

“Look at the formula closely. Since we know last year’s EPS or next year’s consensus EPS estimate, we need only to estimate the appropriate P/E. But since we know the earnings, the denominator, the only unknown is the appropriate share price, or the “P” of P/E. We are therefore left with a useless tautology: to estimate value we require an estimate of value”

The multiple not only fails in doing its job, but it also fails in capturing very relevant business’ fundamentals for assessing their value:

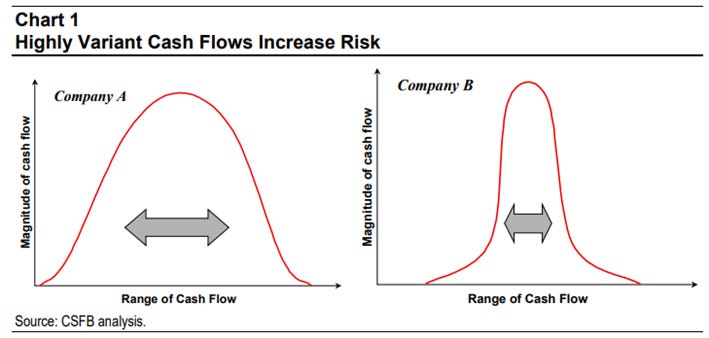

Risk. Two companies with the same earnings and same expected free cash flows can have dramatically different potential future scenarios. The P/E multiple fails to capture the dispersion of outcomes, and wider dispersion highly increases cash flows’ risk. From the following chart, company B should be more valuable as it has much higher chances of falling into the average expected FCF.

Different competitive advantage periods. P/Es embed in them the market’s view on companies’ CAPs. But it is value that determines them, not otherwise.

Investment requirements. P/E multiples offer the same valuation metric to companies that could have absurdly different investment requirements. And, not only this, but because P/Es are based on earnings, they differ from cash flow on some regards. The first layer is on net working capital:

i. For companies with expanding receivables, revenues overstate cash flow from sales

ii. For companies with expanding inventory levels, COGS understate the cash outflow for inventory

iii. Expenses overstate cash outflow by the amount of the increase in accounts payable

The second one is on fixed assets:

I. Depreciation is not an actual cash outflow

II. Capital expenditures are not even included in income statements!

Finally, the P/E multiple is based on a single period of earnings, either trailing or forward. It completely ignores the fact that the market takes the long term view when valuing businesses.

“As a consequence of these differences, earnings fail to measure shareholder value. Further, and to the surprise of many, we show that earnings growth does not necessarily lead to higher shareholder value or a stock price increase”

Personal commentary

The article ended up being more extensive than usual because I still don’t see it very clearly and because the topic to address was much broader than I thought at the beginning. Additionally, I wanted to take the time to properly build a document we could recur to, and I feel it will do that job well, even if there are still things lacking. It was a tough one to write, but hope you enjoyed the piece!

Contact: giulianomana@0to1stockmarket.com

Thank you my friend ! I appreciate your insights...

Great summary! I always find it difficult to choose the right ratio or metrics to evaluate a company. Thanks for sharing!