On Monday, my friends from World Stocksinvited me to their podcast (it’s in Spanish). The topic in question was if Threads could be capable of displacing Twitter.

I generally think better when writing, so I wrote a draft on what I believed could happen until I got to a decisive point. If Threads is a copy of Twitter, it really depends on the latter’s MOAT, which is based on network effects. But how strong is Twitter’s MOAT? And what are network effects at the most fundamental level? Sualem found a fascinating article about the subject, which I’ll be summarizing here.

Short disclosure: I think they’ll be different. The next Twitter is Twitter.

Definition

Network effects imply for a product or service to become more valuable as usage increases. That’s the strict definition. However, over time, there have been many technological services that do benefit from network effects, but different ones, meaning there’s several types of them.

Concretely, people have identified over 15 types of network effects, which revealed my complete ignorance about the matter.

Direct network effects

Direct network effects is one of the five broad categories. These are the strongest network effects and the ones that perfectly adapt to the strict definition. The more people use the product, the more value users perceive and the more valuable the network becomes. Direct network effects were the first ones to ever be spotted. The event occurred in 1908, by AT&T’s CEO. In his shareholder letter, he wrote:

Truly dazzling realization. What’s even more curious is that it was not until the 1970s that the concept was properly defined. In 1972, Metcalfe put the idea together and inferred that, if each node is connected to every other node in the network, the network’s value is n^2.

30 years later, an MIT computer scientist, David Reed, arrived to the conclusion that Metcalfe’s law understated the true value of networks. David claimed that, within a large network, multiple sub-networks can have place. Many networks are truly networks of networks, which made him realize that the network’s value increases exponentially. Reed’s law states that it is equal to 2^n.

A simple example we came up with is WhatsApp. Meta’s messaging app is a network of networks. It allows you to privately connect with people, but it also allows you to create groups within it. The more groups you have, the more value you are receiving from the network. Furthermore, the cost of switching provider increases as well. It’s not only that your friends might utilize it, but also that you have your work and soccer groups. To access both, network’s usage is required.

Within the category of direct network effects, the one that called most my attention is physical nfx. Physical direct network effects are the ones that result and are tied to physical nodes and wires. The best example here is AT&T’s with the extract above.

The value of the network increases as more physical nodes are included. In the telephone’s case, more nodes imply a larger area of coverage, which brings together more potential connections for existent users. Physical network effects are very hard to compete with because they require a huge upfront investment in order to build the infrastructure. Some other examples are railroads, electricity, broadband internet.

2-sided network effects

The second broad category is the 2-sided. This encompasses products or platforms with two types of users, the supply and demand. Each of both comes to the platform for different reasons, but they add value to their counterparts. The easiest example is a marketplace, where more suppliers mean more diversity of products/services that might appeal to a broader demand. Similarly, more buyers bring more overall and aggregated demand, which helps include more suppliers in the equation.

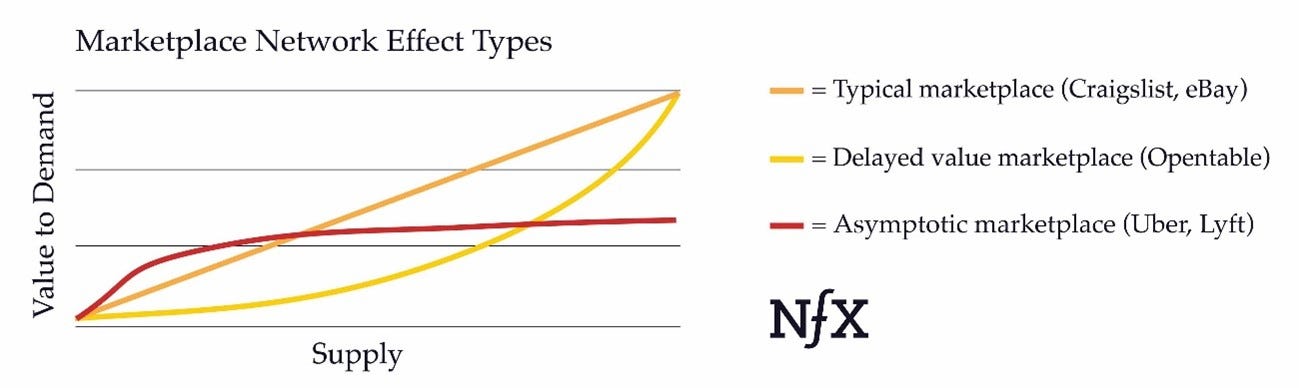

However, what’s interesting here is that not all marketplaces benefit from the same network effect, or not in the same regard. A distinction can be made when analyzing how much value does increased supply adds to the demand side.

A typical marketplace is the one that, no matter how large the network is, an increase in supply adds the same value as before to the demand-side. As time goes by, these get very strong.

A delayed value marketplace is one that has to first accumulate a large base of supply without adding much value to demand, but, after a certain point, demand’s perceived value increases exponentially. Opentable is to make online reservations, read restaurant reviews and earn points towards free meals.

An asymptotic marketplaces is one that has some sort of natural ceiling. There’s a point after which increasing supply does not add much value to demand. In Uber, it is the same for the consumer to wait 4 or 2 minutes, not even to mention less than that. Below a certain threshold, law of diminishing returns drastically strikes. These types of marketplaces are the easiest to compete with.

Personal commentary

We didn’t even cover 20% of the article, that’s how complex ‘straightforward’ things are. The closer you look at something, the more questions arise. I really enjoyed the podcast, reading and writing about network effects. Hope you experienced an alike feeling with the article!