I read Keynes’ book in May and thought I might want to work out my opinion thereon. I’m neither a politician nor an economist. The following is just my impression of his work, done as critically and objectively as I can. I’ll first cover tangential ideas and then share my view on the book’s intellectual merits, if any.

Go to the Source

The misrepresentation of ideas is widespread and something I’ve repeatedly encountered. Most people read “recent” literature, ignoring its origin. I believe this is something to avoid if one were to aim for sound thinking. Once ideas are out there, ‘new work’ is typically an interpretation about these, with some new thoughts.

Problematically, new work brings along the writer’s biases. Even if a good thinker, able to faithfully reproduce the original content, no replicating mechanism is perfect. Furthermore, new work built on top of it will accentuate discrepancies, and so on to infinity. People reading recent literature completely miss what the idea was originally about.

Theory and Logic

Isaac Newton, after Galileo, Keppler, and other giants, did a great service to humanity. He built a theory for how the world largely works; a theory being a framework that explains what causes what and why. In physics, you can test theories’ Truthfulness, or at least have more tools therefor. Nature tells you.

Before you successfully test and retest your theory, it’s just a hypothesis. The problem arose from people becoming so acquainted with the word “Theory” that they just throw it around as if it was nothing. Outside of physics, you just cannot tell; you can’t really test it. And more people agreeing on it, all of them based on illusionary interdependencies, will not make it True.

Quality is something that escapes the grasp of any given sense or ability, but it’s found at the intersection of them all. I’m inclined to believe that logic, mostly following some sort of mathematical path, cannot, in and of itself, catapult man into a sound economic framework. Despite me being attuned to Adam Smith’s way of expressing ideas, Truth might be found in a mix of both thinking methods. I’m not really sure what I mean by this, but it felt as if Keynes was continuously pursuing “if statements” until he cornered each variable. And I think that’s a deeply flawed system to explore economics. Logic alone will not suffice to truly understand.

Economics

An honest evaluation of the book’s intellectual merits forces me to observe the great impediments I face when trying to undertake this task objectively, namely: (i) I have almost 100 years of hindsight; (ii) outside of strict academia, most people I’ve heard speak about Keynes was in a negative fashion; (iii) he published it in 1936, after the Great Recession, yet with no recovery on sight.

I found the book interesting in two respects. Being Keynes an intelligent person, he sets the stage very well, addressing the state of economics and the problems it encountered (which validity I ignore, incidentally). In addition, he had a good grasp of how the different concepts interplay with one another, defining and proposing how this may be done so. Some of his premises are sound and, when assumptions are overlaid, Keynes explicitly declares that these are just assumptions; one has to be careful with their use and any conclusion derived therefrom.

Essentially, and hopefully I’m paraphrasing accurately, some of his conclusions were the following:

He believed that maintaining a stable (~fixed) level of money-wages is the most advisable policy, though his view was not fully inflexible.

Under some conditions, employment will change in the same proportion as the quantity of money; and when there is full employment, prices will then change in proportion to the quantity of money. Thus, policy would be to increase the money supply so long as there is not full employment.

He emphasizes that the problem stemmed not, as was mostly believed, from a lack of consumption, but a low volume of investment. Keynes favored the government kickstarting the recovery by undertaking public investments (i.e infrastructure).

In contemporary conditions, the growth of wealth was not aided, as commonly supposed, by the abstinence of the rich, but impeded by it.

He strongly favored taxation for the redistribution of income, especially inheritance taxes, to reduce inequality.

Against international Trade restrictions in general; in favor when needed to protect domestic employment.

Increase “the volume of capital until it ceases to be scarce, so that the functionless investor will no longer receive a bonus; and at a scheme of direct taxation which allows the intelligence and determination and executive skill of the financier, the entrepreneur et hog genus omne (who are certainly so fond of their craft that their labour could be obtained much cheaper than at present), to be harnessed to the service of the community on reasonable terms of reward.”

In favor of increasingly “socializing” investment, whereby the public authority would co-invest alongside the private sector.

[In an example of an economy with 10M people, 9M of whom are employed], “the complaint against the present system is not that these 9M men ought to be employed on different tasks, but that tasks should be available for the remaining 1M men.”

Keynes thought that, should the policymaker implement the correct measures, the state of the economy would trend towards a more desirable place. When the convergence is manifesting itself into reality, Keynes pointed out that Classical Theory was to take over policymaking once again.

My critique is that, inasmuch as the latter never unfolds fully, intervention would be indefinite. After I mentioned this to a friend of mine, he proceeded to tell me an anecdote:

In the 60s, Milton Friedman was visiting an Asian country. Somewhere he was passing by, he witnessed many workers using shovels to build a road. Friedman’s curiosity was sparked, so he asked a government agent who joined him during that trip, ‘Why are these people using shovels instead of machinery? It could be done faster and with less workers.’ The government official replied that it was to create jobs. ‘Then,’ Friedman said, ‘Why wouldn’t you give them spoons?’

My Take

Upon my first impression, I thought he was delusional. Time has revealed to me that he was not. Insofar as one takes his ideas in the complete context he describes, and under the assumption that he was an honest, objective, intellectual, he might not have been wrong on some things.

It is the general belief, I presume, among the economists’ community, that it was Keynes’ ideas, accidentally, what got the US back on its feet. I believe WWII propelled the US government into the incurrence of massive capital expenditures, financed with money printing. The war forced the government to increase public spending, creating many new jobs, albeit temporary, in the process. By the nature and caprice of things, this might’ve kickstarted the economic machinery.

In the event that the foregoing were true, his ideas might thus be opportunistically right. In a recessionary economy, public spending could be the stepping stone leading to an economic recovery. However, Argentina has persistently undergone economic struggle and Keynesian ideas not only did not save them, but exacerbated Argentina’s issues.

The American peoples chose to continue transacting and saving in US dollars even after large amounts thereof were injected. In contrast, I believe that a large percentage of Argentinian peoples, upon encounter with newly issued currency, have historically exchanged it for goods or other stores of wealth. And further, I suspect that an increasing percentage of the economy has not even opted to transact in Argentine Pesos, preferring other forms of payment.

Largely, Argentina’s history is one of defaults and inflation. The population has grown averse to holding the country’s currency. And if the new currency is not used to undertake new ventures or, as soon as earned through labor, gets exchanged for another currency or asset, it merely generates further downward pressure on the Peso. In one way or another, these Pesos find their way back, in ever increasing amounts, to the hands of the employers who continue to operate in this currency. They remunerate workers at rising nominal rates, for real rates plummet after the basket of goods is counterbalanced with more currency, who in turn again get rid of the Pesos.

Hence it remains unclear. The correctness of some Kenyesian ideas might depend on the country’s context and folklore. Inasmuch as he lays down his assumptions and describes the required stage for him to be right, although omitting scenarios where there’s no demand for domestic currency, there is some truth and usefulness in his reasoning. Having said this, the world rarely satisfies the necessary conditions.

Crises and the Marginal Efficiency of Capital

The Marginal Efficiency of Capital (MEC) refers to the rate of return a businessman expects to get from investing an additional unit of capital; it’s conceptually similar to the IRR, but it applies more broadly to the economy, in contrast to the IRR which is utilized to evaluate individual projects.

A remarkable aspect about Keynes’ book is the clarity with which he saw the influence of psychological phenomena upon the economy. Theretofore, it was believed that a rise in the rate of interest, a byproduct of increasing demand for money, was the largest explanatory factor behind crises.

However, Keynes posits that the main element behind crises is “a sudden collapse in the marginal efficiency of capital.” Though the rate of interest embodies the cost of capital an investment might have, it does not, in and of itself, determine the expected return; if anything, it might only increase the hurdle rate. Expected returns are driven by businessmen expectations for the economy. Well substantiated or not, there are no True answers.

In The Lessons of History, by Will Durant and Ariel Durant, it is very well captured why revolutions destroy wealth, by and large. Inasmuch as most wealth exists in a theoretical fashion, without there being a possibility of materializing all existing wealth at once, a revolution, insofar as it compromises the confidence upon which the whole societal system is built, destroys wealth. Take a stab at public confidence and the world crumbles.

For the Investor

The book is, at times, a useful read for an investor. Keynes speaks about markets with unusual perspicacity and clarity, insomuch that, should the book be reduced to merely these observations, it’d be among the most illuminating writings. Specifically, Chapter 12 addresses how the stock market functions, why liquidity ended up being a harmful feature; how, despite the stock market being organized as a channel through which capital should be able to find the most profitable opportunities, incentives ended up perverting the system; the difference between investors and speculators. It further speaks to the way in which investors and businessmen actually operate, assessing the likelihood for scenarios and acting thereupon, and how much the market and some economic variables are driven by people’s psyche.

About the latter, there is something worth thinking about. Keynes speaks about the state of confidence of businessmen and investors as a major factor behind the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital, which resembles an investment schedule. The system’s capital outlay, and thereby, businesses’ individually, runs on a flexible schedule which allocators have. And they think about future incremental deployments as having attached thereto a specific rate of return. In consequence, cycles of contractions and expansion follow, as a byproduct of this state of expectations. Oscillations are severely aggravated by speculators and the market liquidity they’ve been blessed with.

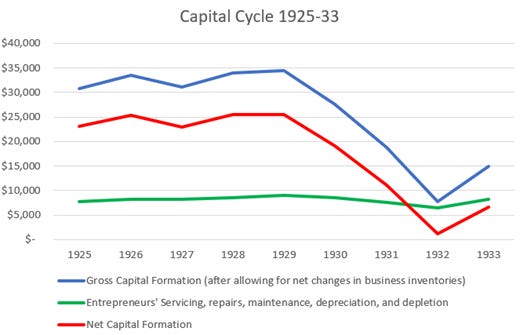

The following chart captures three variables, which could be seen as capital outlay (maybe investment), expenses/maintenance, and net investment, the difference between the former two; a model which, although I don’t fully comprehend it, I found extremely useful;.

Note: In millions

In a non-static economy, the aggregate volume of capital formed, or invested in long-lived assets (houses, buildings, manufacturing plants), varies immensely, greatly influenced by the state of expectation. Brighter periods, such as 1925-29, where vast amounts of capital is deployed, subsequently requires increasing magnitudes of expenses, diminishing future net capital formation unless increasing amounts of capital gets deployed.

By the nature of things, the higher you are, the more distance to the ground. An economy, even resilient in appearance, is underlied by deep fragility; for a single event can unleash a domino effect, affecting the state of expectations, which gets negatively reinforced by former years’ increased levels of investment.

This very well relates to an idea I heard from Mohnish Pabrai: Gestation Periods. Commercial real estate follows something like 5-10yr cycles. When there’s excess demand, investors deploy capital into new buildings. Given the size thereof, 5 years need to go by before this new supply hits the market. In year 2, given supply has not made it to market and excess demand persists, more buildings will be started. The same happens until the first batch of buildings hit the market, whereupon the gap between supply and demand narrows. However, buildings began in year 2/3/4/5 continue increasing supply for the coming 4 years. And until this capacity gets absorbed, which might take 5-10 years, the real estate commercial market will be oversupplied. In a different industry, where constructions may take one year, there’s not such prolonged cycles, for supply catches up more quickly.

Some Wisdom

There is an element in Keynes’ General Theory, typically overlooked, which attests to his, I hope, candidness. Keynes comments about how, all throughout his life, he was taught something, which he longly held as truthful, and even himself taught to others. Time revealed to him how wrong he had been. Upon such epiphany, Keynes saw the need of thinking. Further, the purpose of his book, presumably, was to push for new ideas, very much required at the time, for there was no light. I strongly appreciate this feature, inasmuch as it stretches the limits of societal ideas.

“We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them” Einstein

Thinking differently from the crowds is not only difficult given the broad area the latter has covered throughout history, but the many psychological impediments make it an excruciating task. Masses are seen as safety; everything lying beyond the reach thereof commonly entails risk, and a peculiar way of “stupidity”.

“Worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally”

Physics Envy

It’s still unclear to me how more complex mathematics first crept into economics, but I don’t think any Truth is to be found there. It just doesn’t feel right. What I found interesting in Keynes’ work is that he explicitly and quite eloquently attacks the pseudo-mathematical approach taken in his field.

“Too large a proportion of recent ‘mathematical’ economics are merely concoctions, as imprecise as the initial assumptions they rest on, which allow the author to lose sight of the complexities and interdependencies of the real world in a maze of pretentious and unhelpful symbols.”

False Humility

This is more of a personal observation. Throughout the book, Keynes sometimes notes that he does not hold the absolute Truth on the matter, that there are assumptions and things to consider in reality. I almost never got the feeling that these lines were written sincerely. Additionally, the writing is good, but seems structured in a way so that not everyone would understand it. Both things make me suspect his intentions. I never felt that with Adam Smith or Charles Darwin, whom I consider were faithfully pursuing Truth.

Final Remarks

I am hesitant to recommend Keynes’ book. As I hope to have given the sense in this writing, I learned much, but it always takes time to unlearn what needs to be unlearned. The deeper it gets ingrained, the harder it is. Chapter 12, despite what I felt were plainly wrong conclusions, is an enlightening read. Buffett’s recommendations never miss.

Feel free to reach out if I can help you with anything:

Giulianomana@0to1stockmarket.com

would love your thoughts on some of my stuff. follow me back, I could DM you?