2024 Shareholder Letter

Performance and some thoughts

2024 has come to an end. In this letter, I will report on the partnership’s yearly performance and share some thoughts. Given the fact I have not had many good ideas, or ones worth exploring, in the recent past, this writing will be shorter than in previous years.

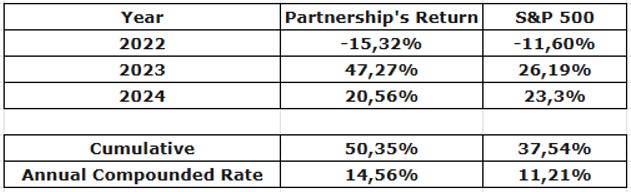

During 2024, the partnership returned 20.56%, bringing the return since inception (25th of Jan, 2022) to 50.3%. After fees, the partnership’s return since inception has been 45.3%. Although I’m not mindful of how other instruments or “comparables” perform, there is some truth in that they give a general sense of how the sea fared. A tideless sea makes surfing impossible, although you might find some tides in obscure places. The obverse is likewise true. On a tropical island, you’ll find much more fruit than in boreal forests.

The S&P 500 returned 23.3% in 2024. The index’s return since the partnership began has been 37.54%, or 11.2% per annum.

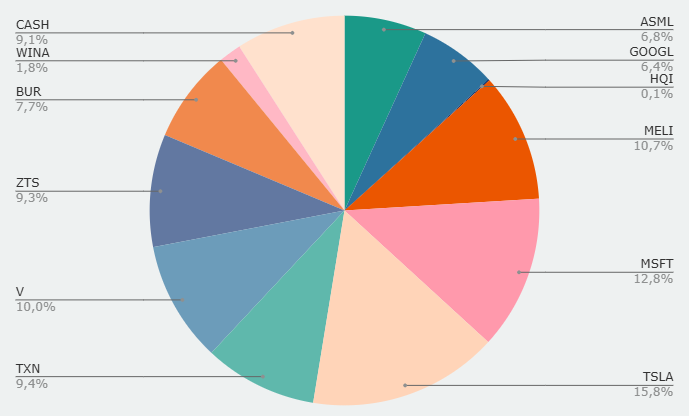

As of January 2025, the portfolio looks like the following chart illustrates. I do not think I have anything novel to share with regard to the different positions and their sizing. I would encourage you to revisit previous quarterly writings.

Conviction or Arrogance?

It has been my experience that, whenever I make up my mind that a business is mispriced, I find it incredibly hard to think otherwise. Much of the human brain is wired to impede one’s reality from vanishing, and a very pragmatic way to do so is by filling it with biases, one of which is the confirmation bias. Once you arrive at a conclusion, your inner self will work intensely to accommodate new information so that it suits your formerly held beliefs.

Changing is obnoxiously hard. On average, this works perfectly, but when you start analyzing events singularly, you’ll observe a much better job could have been done had the person been aware of how stupid their actions were. Intelligence does not prevent this a single bit; my estimate is that it mostly exacerbates it unless you exceed a threshold of brilliance, something I’ve observed after studying numerous physicists. Falling short of it, intelligence is more hurtful than useful in this respect.

There have been a few instances where I have confidently thought a security’s market price was well below its intrinsic value, whereupon we invested in these handfuls of companies. Thus far, events have turned out all right, in general, giving the impression that the analyses had been well done.

However, it is of the utmost importance to acknowledge that markets, and economies, have never done as well as in the past 150 years. Furthermore, considering the effects of compounding, the past 2 decades have been extremely tilted towards the upside in a rather fantastical — in the traditional sense of the word— fashion. 21st-century investors resemble fruit gatherers on a tropical island.

From common sense and logic follow that the path transited heretofore will likely not be walked hereafter. Over the past century, global GDP, especially in the US, grew at outsized rates, now reaching astronomical numbers in absolute terms. Moreover, equity markets outpaced GDP growth mostly due to corporate profits growing at higher rates than GDP. Inevitably, margin and cash generation capacity will reach a point where it’ll be impossible to improve upon. My suspicion is that the trend thereafter will be downward, as new competition joins and climbs the margin ladder, if it ever does.

In this environment, where Society’s wealth extraordinarily exceeds anything the world has seen, one must critically assess the correctness of their analyses. Not only is it easier to do well when everything does well, but it is easier to do well when people’s expectations are built on the recent past.

Even if both elements contribute to a business’ returns exceeding those of the general market, the correctness of the analysis is yet to be determined. Until the company’s future manifests itself, naturally taking decades, profits for the investor will be just driven by people’s change in expectations.

Conclusively, I’m still alert. Despite the fact that some of the decisions made in the past 3 years have yielded decent results, much remains undecidable and will probably be so longly hereafter. I think a person who doesn’t remind themselves about the ever-existing element of uncertainty will unequivocally tend to reach erroneous conclusions and a misappreciation of the past.

I try not to fall into the arrogant area, but I’m not so sure I do a good job at it. I realize that I can be wrong, but when I think about a position I might’ve held for 3 years with no results, I do not think I’m wrong; I just think it will take more time. This goes beyond companies for which I might’ve paid too high a price. That’s easily recognizable after the fact. But it’s the gray ones that are the difficult ones. Presuming I did not pay too high a price and that I’m right on the idea, how long can the wait be until it manifests itself?

Incidentally, in one of Greenblatt’s interviews, I heard him say something along the lines of ‘our research shows that 90% of true discrepancies between value and price tend to narrow/close within 3 years’. That really made me think. Will I be able to recognize one of these mistakes and cease holding them?

Exposure to Luck

For the purpose of this writing, let’s define luck as favorable randomness; that is, things that fall out of the cause-and-effect spectrum and end up benefiting us in one way or another. It would be ideal if one could purposedly build an attractor of luck. More specifically, if one could tilt the future outcome distribution towards the tail that most favors us.

I found Howard Marks to be one of the great articulators of the concept of risk. Risk relates to the understanding that ‘many things can happen, but only one will happen.’ When you roll a dice, you can get either {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}. However, even when you know the potential outcomes and their probability of occurrence (16.6%), you still don’t know what will happen until after you roll the dice.

“We live in the sample, not the universe”

The added problem that investing posits is that you don’t really know what can happen. It feels like the completeness of the field lies in the unknown and unknowable world. An infinite number of variables interact with one another, with tiny changes at a node shaking the whole system, and unspecified locations for the nodes composing each puzzle. How to thrive in such an environment remains obscure, but there is one insight worth pondering.

Every time one makes an investment, it metaphorically resembles buying a lottery ticket. When the time arrives for the winner to be announced, a jar is shuffled, and a ticket is picked out from the thousands contained in the jar. Howard observed that superior investors have a better sense of the tickets in a jar. They know which lottery has the outcome distribution skewed towards profit. They do not play fair lotteries.

That’s the reason why knowledge and research are highly valued. Every piece of the puzzle one can gather will help make a better assessment of the ticket distribution within jars. Ideas like the margin of safety, competitive advantage period, equilibriums, competitive dynamics, manager’s talent, and so on, help make an informed inference. When considered, these ideas can be critical in determining a crucial aspect of investing: Which lotteries not to join.

Investing has an asymmetrical structure of payoffs, and with future results compounding on prior ones. Therefore, even though an investor might get a decade of a 30% CAGR, if that person deploys all capital in a business that goes bankrupt, their final result will be a total loss. It doesn’t matter how well they’ve done in the past, but how well they can do going forward, and whether they’re capable of preserving the wealth acquired.

This is the only profession I can think of that, by stacking yearly averages, you can get superior results because of that fact. It’s a peculiar characteristic that carries with it investors’ necessity to remain alert.

“We have never had a year below the 47th percentile over that period or, until 1990, above the 27th percentile. As a result, we are in the fourth percentile for the fourteen year period as a whole.”

Correctness vs Accuracy

If you bet on preciseness, you’ll inevitably be wrong. I largely believe it has been a massive mistake for disciplines to try to imitate physics. Mathematics is a tool for logicians to understand a world full patterns, of sequentially sensible steps. However, when you do not know all variables impacting the output or their magnitude, it becomes a mostly useless tool.

There’s a book I read in 2024 that pushed me further in this line called Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Its second half is about answering a profound question: What is Quality?

Pirsig concludes that Quality is something that escapes all dimensions on which our perceptive system makes assessments, but it’s at the point where all intersect. Quality is something that we cannot define, but we know if it’s there. It’s something we see, yet it is invisible; something we hear, yet it makes no sound. It does not make it to our self through intuition, thinking, or emotion, but it somehow gets to us. We unknowingly sense Quality.

I believe the investment profession could be largely better practiced from that standpoint. Ideas such as the ones aforementioned can be perceived, understood, and can largely help one form an opinion. But a mathematical connection? No. A sequential chain of logic steps to pin down any of those? No. Chains always break somewhere. Investing has lately appeared to me as some sort of juggling of useful concepts and training the part of the mind that concludes thereupon.

Final Remarks

What goes on within one’s mind remains obscure, yet I find that recurrent, deliberate, analyses thereof are fundamental to avoid falling into one of its many traps. The investing profession is of true fascination to myself, for it allows a continuous sharpening of one’s skills. It further forces a unique kind of mental activity which I find enjoyable.

My intention in these writings is to update the reader on the framework I utilize for investing, at least to the best of my capacity. Transparency in the thinking process, and how it evolves, should lead to a more acute judgment of the partnership’s outlook. Future results turn dark whenever we stop learning.

More importantly, I’ve been placing more emphasis on making my writing as concise as possible. I have not had many interesting thoughts directly related to portfolio management, and digressing too much from it feels unfaithful to you.